We often hear organic wine growers saying that the organic way of thinking should continue in the cellar. But what does that mean?

The rules for organic wine in the cellar has to do with what additives and techniques you are allowed during the vinification to assure that the production of the wine runs as smoothly as possible. These rules were introduced in 2012 when the term “organic wine” was created. Before 2012, everyone was following the same rules in the wine cellar, but with the then new denomination “organic wine” the rules for winemaking for the organic producers became more restrictive.

By and large, these are not any strange processes or products. But big headlines in newspapers shouting “70 different additives in wine!” makes people wonder. Are there really that many additives in a wine? Is wine concocted by blending a whole lot of different “ingredients”? Of course not.

Some 70 products are allowed for conventional producers. But no one uses them all.The rules for organic producers are more restrictive and allow fewer products. Most winemakers only use a small number of them, at most.

It is essentially mainly products that, above all, are used to make sure that the fermentation goes well and that the wine is clean and stable in the end. It is not a question of “ingredients” in the sense you use when, for instance, you make bread, where often you add both water, sugar and salt as well as various flavourings. Instead, it is about making sure that the grapes ferment in a normal and safe way and ends up as a correct wine.

Some of these products are better suited for a particular climate, for red wines or white wines, depending on the circumstances and the purpose. For every intervention, there are many different options. For clarification, for example, there are 19 different possible products. You choose one, depending on your situation, or you do without.

This is an article in our eight-part series. Here’s the full series of articles on organic, biodynamic, natural and sustainable:

- Organic, biodynamic and sustainable wine, an overview | part 1

- Organic viticulture: What is it really? | part 2

- Organic wine: in the wine cellar | part 3

- Organic certification | part 4

- Biodynamics: What is it really about? | part 5

- Natural wines | part 6

- Sustainable wines | part 7

- The future of organic wines | part 8

- Bonus: Video master class on organic wine

Additives

No one uses additives unnecessarily. If you use an additive, there is a reason. It’s mostly about getting a stable wine that can handle long transports and being exposed on a supermarket shelf. With the addition of sulphur dioxide, the wine will manage. You also want a wine that looks attractive. The vast majority of consumers want their wines to be clear and brilliant in colour. Clarification and filtering ensure that this is the case. Some problematic years you may want to add yeast nutrients to facilitate the fermentation. Producers in warm regions may sometimes need to add tartaric acid to boost the freshness of the wine.

The reason we can buy so many decent wines at low prices today is that it is possible to maintain a stable quality thanks to technology and additives in the cellar. And thus, make it financially viable to keep prices low. The producers can make the wine they want to make and that consumers wish to drink every year. Anyone upset about “70 additives” should simply refrain from buying the cheapest wines. It is to some extent so that the higher up in the price range we go, the fewer interventions are made.

To a certain limit. Even expensive wines must withstand long transports, and they need to be stable. A chateau owner in Bordeaux wants his wine to taste the way he intended it to when it is drunk on the other side of the globe. His clientele is probably quite sensitive to off-flavours and post-fermentation effects in the bottle. The oft-repeated cliché that “almost all high-quality wines are made with organic or biodynamic or natural) methods” is quite simply a myth.

You can organise the additives that are used in a few approximate groups:

- “Stabilisation”, of the must and of the wine, to avoid that it becomes subject to various defects (e.g. becomes vinegar)

- Fermentation: or in other words, yeast

- Fermentation facilitators

- Adjustment of the acidity and tannin levels

- Enrichment, to raise the alcohol level (often in a simplified way called chaptalisation)

- Adjusting/stabilising the colour

- Raising the sugar level

- Removing certain specific defects

- Clarification and filtration aids

Very few of these are “flavouring”, affecting the flavour directly. To some extent, one can say that acidity adjustment does that, making the wine taste more “fresh” and avoiding a dull character, equally tannin. The only product that really to a substantial effect does have a direct “flavouring” impact on wine is… oak. To use oak barrels (or some oak derivatives) is a way to flavour the wine with aromas extracted from the oak. The oak contributes several other things to the wine too, of course.

In a way, this focus on “additives” in wine is a bit odd. Almost all foodstuff, bread, yoghurt, paté, sausage etc, is made with different ingredients and different additives to a far greater extent than wine.

Most of the additives or process aids used in winemaking are widely used in other food production and can frequently be seen in everyday foodstuff.

Ingredients on the label

The question of ingredients on wine labels has been debated extensively in recent years. However, it is not entirely obvious what should be considered an ingredient.

The EU has now defined which are “additives” and what are “processing aids”. An additive remains in the wine and would thus be named on a “list of ingredients” on the label. One example is sulphites; another is acidity. A processing aid, on the other hand, is removed from the wine before bottling, so it would not need to be named. An example is various clarifiers and enzymes of which there is nothing left in the bottle.

When the EU was to determine the rules for vinification for organic wine, they needed to decide which additives and processing aids should be allowed, but also which of the different techniques used in the wine cellar should be considered sufficiently organic.

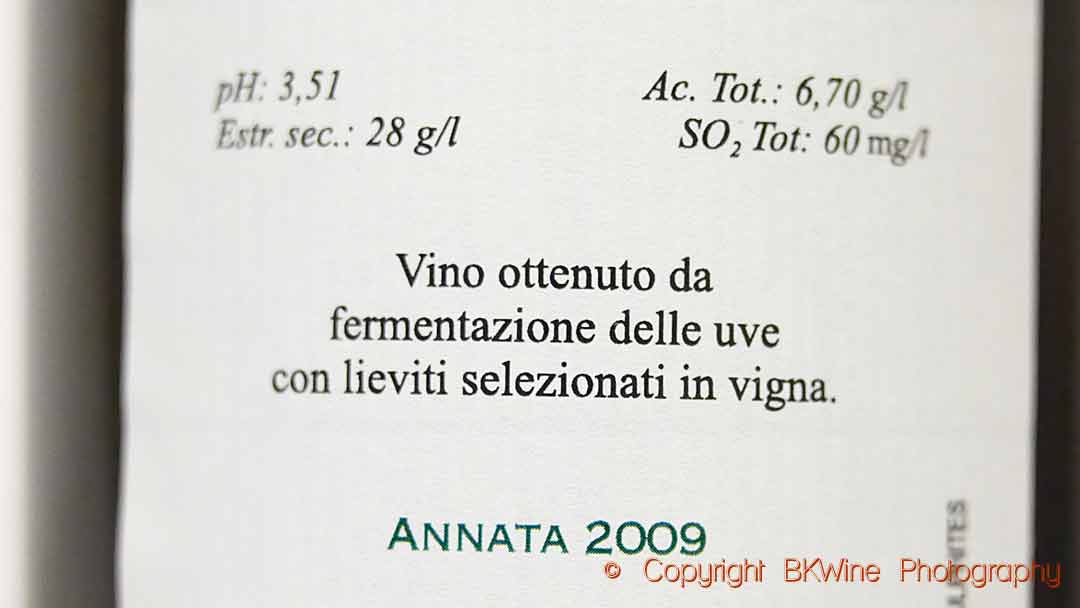

Let’s also address another common misunderstanding. We often hear or read “the EU does not allow wine producers to put a list of ingredients on the label; the EU forbids it”. This is a myth; it is not true. The truth is that alcoholic beverages have an exemption from the obligation to have a list of ingredients, so it is not compulsory. But if you want to put a list of ingredients on your wine label, you are allowed to do it. No problem. However, if you do, you must follow the general rules about how a list of ingredients should look. It’s also worth pointing out that what is sometimes touted as a list of ingredients on wine labels (often with the mistaken addition “in spite of that it is forbidden”) is no more than a chemical analysis and not a list of ingredients (listing alcohol contents, acidity, dry matter etc).

Organic rules in the cellar

It is easier to decide what should be banned in the vineyard than in the wine cellar. But in 2012, the EU countries agreed on an organic regulatory framework for vinification. “Wine made from organically grown grapes”, as it was called before that date, became “organic wine”. As a result, today “wine made from organic grapes” is not a permitted denomination.

There is no big difference in what an organic grower can do in the wine cellar compared to a conventional one. Sometimes it feels a bit erratic, difficult to understand why some things are allowed and not others. I can understand that in a way. Because, what makes a wine organic? The vinification does not have the same impact on the environment as spraying in the vineyard.

Before the 2012 decision, the EU conducted surveys to find out what consumers think. And it turned out that for many, an organic wine should be as “natural” and “authentic” as possible. These are vague words, and when you add the political game, it is quite an achievement that they managed to agree on rules for vinification at all.

The result was a set of rules that some people think is far too generous. Each organic wine producer needs to decide which permitted additives he/she wants to use. The decision will depend on different things; the style of wine, the price, the quantities, the weather conditions.

Of the around 70 additives, process aids and technologies that are allowed for conventional growers, just over two-thirds are also allowed for the organic ones. Some additives must be organically certified to be used, e.g. cultured yeast and sugar. In some cases, the permitted amount is lower, as for sulphur dioxide. For certain types of filters, e.g. tangential filter, a minimum size of the pores is prescribed. Some synthetically produced products are prohibited for the organic producers, such as the plastic product PVPP (a processing aid) which stabilises the colour in white wines and rosé.

Sulphur

No other additive has received as much attention in recent times as sulphur. Virtually everyone agrees that there is no better way to stabilise the wine. To “stabilise” the wine means that you make sure it will not be subject to problems, such as post-bottling fermentation, attack by acetobacter etc. And yet it has almost become an insult in some circles.

Sulphur, in the form of sulphur dioxide, is added to stabilise the wine and to prevent it from oxidising prematurely. It also acts as a microbiological stabiliser. There are rules for how much sulphur the wine can contain at the time of bottling.

The organic growers have to cope with less sulphur than the conventional ones, 30 milligrams per litre less. For organic wines, there is also a category that applies to wines with less than 2 grams of residual sugar per litre, which does not apply to conventional wines.

A conventional white wine with five grams of residual sugar or less may contain a maximum of 200 mg of sulphur dioxide. The corresponding organic wine may contain a maximum of 170 mg. If the organic wine has 2 grams or less of residual sugar, the limit is 150 mg.

A conventional red wine with five grams of residual sugar or less may contain a maximum of 150 mg of sulphur dioxide. The corresponding organic wine may contain a maximum of 120 mg. If the organic wine has only 2 grams or less of residual sugar, the limit is 100 mg.

For sweet wines, a few higher levels of sulphur dioxide is allowed, depending on the wine type. The highest permitted level is 370 mg for botrytised wines. (There is a higher risk of problems in sweet wines, e.g. post-bottling fermentation.)

It is worth noting that many producers today, both conventional and organic, are below, sometimes far below, these permitted limits.

The levels define how much is allowed in the bottle, not how much you are allowed to add (wine naturally contains some sulphur, even without it being added). One often refers to “sulphur” in the wine, but it is really the analytical level of sulphur dioxide, often called sulphite.

To entirely refrain from sulphur is very unusual. The producer risks not only putting an unstable wine on the market. The taste can also be affected and change. A wine without added sulphur sometimes completely loses its terroir character, the sense of its origin.

Yeast: wild or added

The cultured yeast, sometimes called selected yeast or industrial yeast, has also been through some hard times recently. According to natural wine enthusiasts (more about natural wine in a later article), only fermentation with wild yeast (the “naturally occurring” ambient yeast) is acceptable, so, fermentation without any added yeast. It is odd that there has been such a debate about yeast. It should be an uncontroversial addition. The yeast you add is still natural; it is not a chemical product made in a laboratory. The culture yeast is simply a naturally occurring yeast that has been identified and selected based on some desired qualities, for example, that it manages to ferment high levels of sugar. It has then been “cultured” to produce it in larger quantities. It is a process that is similar to what is done with vines: you identify vines in the vineyard that have desired qualities, e.g. the best fruit, the most resistant, and then you take cuttings and propagate it. There’s not really anything “artificial” with cultured yeast.

The organic growers are allowed to add cultured yeast, and many do. The yeast must be organic if the strain of yeast you want is available as organic.

The cultured yeast has, for a long time, dominated the wine industry. And it still dominates, even if the wild yeast gains ground. It is hard to know the exact figures, but a guess is that at least 90% of all wine is made with cultured yeast, including many of the most exclusive and famous wines.

What is best is impossible to say. An argument for wild yeast is that it better shows the terroir and the origin. Maybe it does, but it’s hard to be sure. Terroir is a vague concept.

However, the risks with wild yeast are higher. The start of the fermentation can be slower with the risk of off-flavours developing, or that other undesirable microorganism may get the upper hand. The fermentation could stop before the yeast has eaten all the sugar, so-called stuck fermentation, if the natural yeast is not energetic enough. But as always, it depends. Some producers never have problems with wild yeast and wouldn’t use anything else, and make fantastic wines. Others would not be able to sleep at night if they used it.

There is no cultured yeast that is “aromatic” or “flavoured”. The yeast does not, as such, add flavours. However, some yeast enhances certain aromas of a grape. So the choice of yeast can affect the style of the wine. There is a variety of yeast on the market. They suit different grapes, different climates, different wine styles. For example, there are yeast strains that enhance the aromatic character in sauvignon blanc, and there are others that underline the volume given to a wine with barrel ageing. There is also cultured yeasts that give particularly low levels of sulphur in the wine for those who worry about sulphur levels. But yeast can also be “neutral”.

If you want to make a wine for a specific market with specific taste preferences, you would carefully select your yeast. But even if you want a yeast that is neutral and does what it is supposed to – eat the sugar and make alcohol – and nothing else, you choose one that is suitable for your wines.

What is really needed?

Most organic producers keep the interventions to a minimum. How much help they need from technology and additives depends on the type of wine they are making and the particular situation. Who are they selling to and at what price? If you have healthy grapes, a reasonably small yield and the weather has been beautiful, then you have a higher chance of coping with just a few interventions than if you have damaged grapes from large yields or lousy weather. Some of the techniques and aids can in a difficult situation make the difference between getting an acceptable wine and on that is of bad quality due to e.g. terrible weather.

An example of organic vinification

Here’s an example of what could happen during the vinification in an organic wine cellar. The grapes have just been harvested. Both manual and mechanical harvesting is possible. (There is no requirement for hand-harvesting for organic wine. It is not obvious that manual harvest is better than machine harvest. Read our article on the advantages and drawbacks of manual harvest compared to mechanical harvest.)

If it has been a cool year, enrichment with a little bit of sugar (chaptalisation) or with concentrated grape must may be needed. The same rules apply here for the organic growers as for the conventional ones. The organics can also use reverse osmosis, an advanced technology, to concentrate the must.

Cultured yeast is added if desired, and, if necessary, some type of yeast nutrient to help the fermentation. Yeast nutrition can be cell walls from Saccharomyces cerevisiae or inactive yeast. Some enzymes can be added to facilitate the extraction. The enzymes for this purpose are proteins produced from cultured fungal organisms. Temperature control during fermentation is of course allowed.

In a hot region, you may need to acidify in some hot years, i.e. add some sort of acid, usually tartaric acid (which is derived from wine).

Lactic acid bacteria can be added, if desired, to facilitate or accelerate the malolactic fermentation.

Stabilising the wine is important. Sulphur dioxide and other sulphur compounds can be added throughout the vinification, albeit in smaller amounts than the EU general rules (as above). You can stabilise microbiologically by quickly heating the wine to 70 degrees C, so-called flash pasteurisation. The temperature limit will be raised to 75 degrees C in 2022. Chitosan, produced from fungal organisms, can be used to remove off-flavours from, e.g. Brettanomyces, a type of wild yeast.

The wine can then be aged in the way the winemaker wishes; in oak, concrete, stainless steel, terracotta, etc. If you make inexpensive wines but still want a little oak character, you are free to use oak chips or staves.

White wines can be clarified with bentonite and red ones with “egg whites”, usually in the form of albumin powder. To avoid using an allergen (albumin), some use a pea protein instead. It is also allowed, but much more unusual, to use gelatine or isinglass as a clarifying agent. Since these are fining aids (to clarify the wine) that combine to create larger protein molecules with elements in the wine that can cause impurities they are removed before bottling and do not end up in the bottle. Tannin (from grape skins or wood) can be added to facilitate the clarification and at the same time improve the structure of the wine.

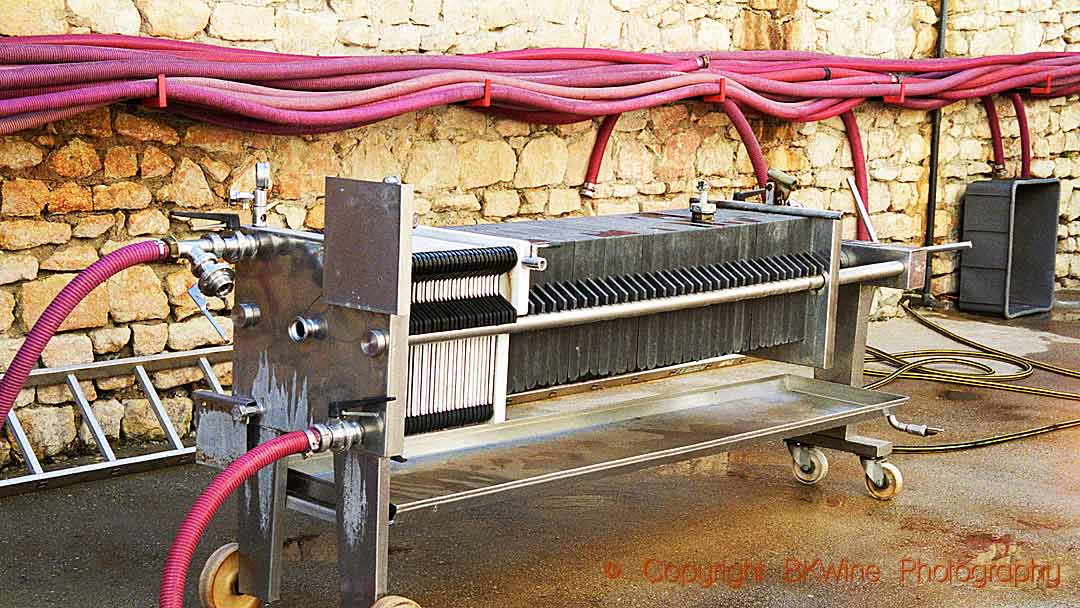

A light filtration does not damage the wine. But, as with clarification, filtration is not done systematically. It can vary from year to year. You can use kieselguhr (a clay), cellulose plates or a tangential filter, the latter with special requirements for the size of the pores (> 0.2 microns). Some people say that filtering the wine may remove some flavours, but there is scant scientific evidence for that.

Stabilisation of the colour can be done with gum arabic, a gum resin from an African acacia tree. Tartaric acid stabilisation of white wines is done with cold stabilisation to avoid the risk of “wine crystals” (harmless tartaric crystal deposits due to high levels of acidity) in the bottle.

You can bottle your wine in a glass bottle, plastic bottle or a box, with the type of closure you want. You can also sell your organic wine in bulk.

We should point out that all this is just examples. A producer may do none of this or just some of it.

This is how it can be done. But the interventions can also be fewer. All organic winemakers have their own philosophy.

And remember, not even the most inexpensive wine has 70 additives.

With this and the previous article, Organic viticulture, what is it really? | part 2 , you should have a good grip on what organic wine really is.

And remember:

- There’s just one common definition of what “organic wine” means in the EU; it’s the same in all countries (most other countries follow the same rules, except the US that is slightly different)

- If the wine sold as “organic” in the EU, then it follows these rules disregarding which country it comes from

- If a wine claims to be organic, then it must be “certified”, be controlled and have an organic stamp. We’ll come back to that in a later article.

- Organic is not the same as biodynamic, sustainable or natural

The following articles will explain these concepts more in detail.

Don’t miss the other articles in this series on organics, biodynamics, sustainable, and natural wines. See the list at the beginning of this article.cles in this series (see the list at the top of this page).

If you want to know more about this subject you can read our book “Biodynamic, Organic and Natural Winemaking”.