Although organic farming is increasing, it is still what we call conventional agriculture that dominates, where you can use synthetic chemical products. Therefore, organic producers need to be able to prove that they work organically according to the official rules of the EU. To get this proof, you have to obtain a certification. You then have the right to put on the label and in your marketing material that you are organic. If you are not certified, you are not allowed to claim to be organic.

Of course, you can practice organic farming regardless, without certification. But in that case, you will not be allowed to label your wines as organic. It is hard to say how widespread this is. And it is not easy to know if those producers are truly organic. Without certification there is no control. It is up to consumers to decide which producers they want to trust.

This is an article in our eight-part series. Here’s the full series of articles on organic, biodynamic, natural and sustainable:

- Organic, biodynamic and sustainable wine, an overview | part 1

- Organic viticulture: What is it really? | part 2

- Organic wine: in the wine cellar | part 3

- Organic certification | part 4

- Biodynamics: What is it really about? | part 5

- Natural wines | part 6

- Sustainable wines | part 7

- The future of organic wines | part 8

- Bonus: Video master class on organic wine

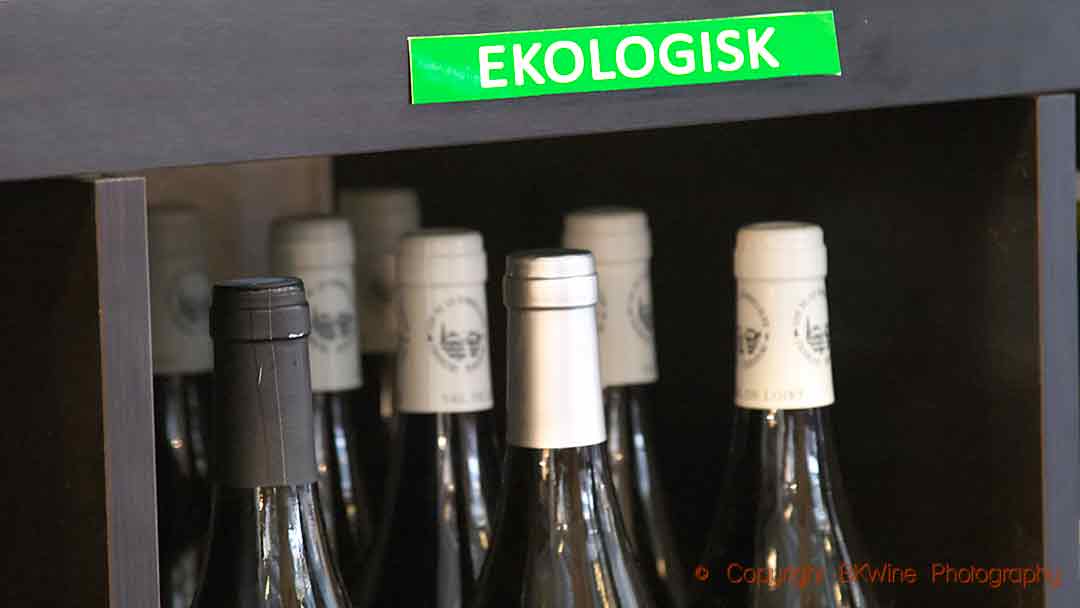

The trend today is that more and more producers are choosing to become certified. Today, wine consumers in many countries are looking for organic wines. It has in some cases become a selling point to be organic. This is a fairly new thing. But still, most of those who convert to organics do it because they think it is a better way to work.

Certification is often a requirement if you want to sell your wines on the export market. It makes it easier not least if you’re going to work with the monopolies in Scandinavia, where the demand for organic products is increasing.

The conversion period

It takes three years before you get your certification. During these three years, you are “under conversion”. If you want, you can start cutting down on the synthetic products little by little even before you start the conversion. But from the first day of conversion, the vineyard and the production must be managed 100% organically, according to the EU rules. This means, for example, no synthetic chemical spraying in the vineyards, no artificial fertiliser and fewer additives during the winemaking.

In other words, before you get an organic certification you must work totally organically during three years. If you at any moment (during the conversion or when having a certification) chose to deviate from the organic rules, for example by using chemical synthetic spraying a difficult year with much downy mildew, then you have to start again from scratch and do a new conversion period.

EU official organic label

To check that the organic growers comply with the rules, each EU country has approved national control agencies. These agencies are private firms, and they carry out annual inspections and issue the organic certificate to the producer every year.

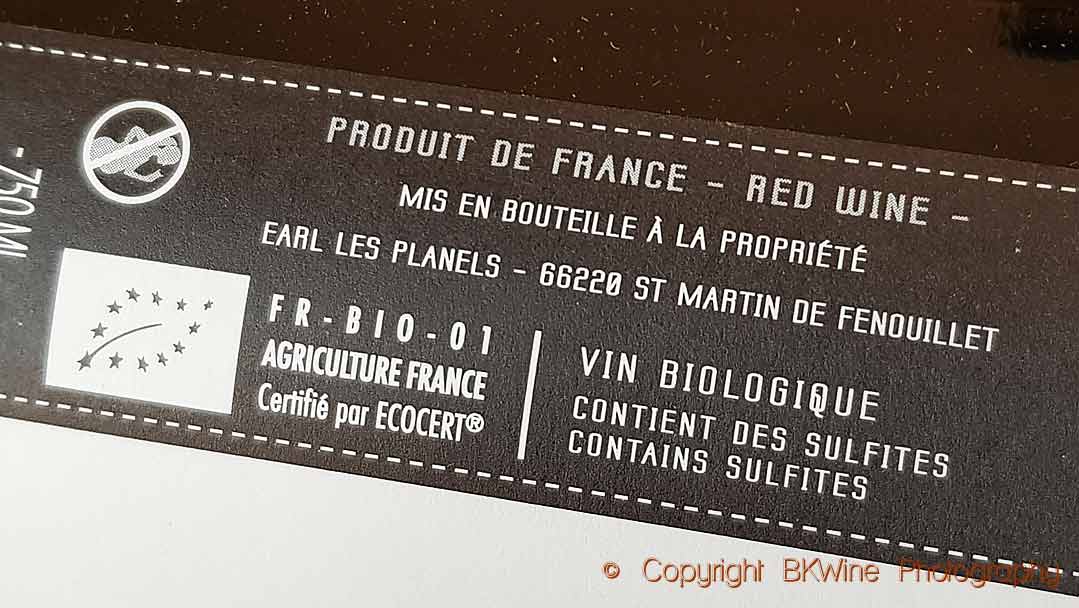

To show their clients that they are organic, wine producers put the EU logo for organic food on the label, “the green euroleaf”. The leaf is mandatory. Of course, you can choose to be organic “in secret” and say nothing about it on the bottle, in other words, get a certification but chose to not mention it. But if you want to say that you are organic, you have to do it with the leaf. If you wish, you can add vin biologique, “organic wine” etc. But the leaf must be on the label.

On French wine bottles, it is also common to see the logo “AB” (agriculture biologique, organic farming) together with the leaf on the label. The French are very familiar with it. It is a label originally created by the French ministry of agriculture but today it simply means that the wine follows the RU rules for organics. It was used frequently on the labels before 2012, so before the leaf. Today you can still use it but only if you also have the EU leaf.

The control bodies

Each EU country has several approved control agencies. France has eleven. Sweden has seven. The label must show which certification organisation it is that has done the control. That is indicated by a code identifying the organisation, for example FR-BIO-01 (for Ecocert in France) or IT-BIO-007 (for Bioagricert in Italy). You can also put the logo and the name of the control body on the label (Ecocert, Bioagricert etc).

The largest certifying control organisation in France is Ecocert, which handles around 75% of the French organic growers. Ecocert also works internationally and is present in 80 different countries.

Each organic farm is controlled at least once a year, and there can be as many as 4-5 inspections. These take place in the vineyard where soil samples are taken for analysis and inside the winery. The accounting and receipts from suppliers are checked. The inspections can be both announced and unannounced. A medium-sized winery pays around 400 euros a year for the controls and the certification. In other words, the fee to be organic is low.

There is today a large number of control bodies. You can find the whole list here. But all follow the same rules, those defined by the EU.

The EU gives subsidies to farmers who convert to organic farming. The farmer undertakes to work organically for at least five years. The grant for a wine producer is around 350-500 euros per hectare and year for five years (the conversion years and two more years).

The certification procedure

When a grower has decided to become organic, he reports this to the authority that registers organic producers in his country. In France, it is Agence Bio. He then chooses a control body and registers with it.

For three years, the wine estate will be “under conversion”. The grower now works 100% organically, but he is not yet allowed to put it on the label. From year two he can put “under conversion” on the label.

How the transition goes depends on how the starting position is, for example, whether you have already gradually reduced the synthetic pesticides or not. It is essential to motivate the whole family and your employees in the process. For everything to work effectively, everyone must agree to work differently. Some go on a training course. The grower may need to analyse the soil to see better in what condition it is and thus be able to plan the work more efficiently.

If you pass the three years without a glitch, you get your certification, and you can proudly put the green leaf on the label. It is also mandatory to put the control agency’s code number on the label. Each country and control agency has its own unique code, as mentioned above.

Every year you get a new certificate.

There is only one organic certification

Sometimes wine writers and others go on about how complicated it is with organic certification, that there are so many different ones and that they are different in each country. In reality, it is the opposite. In Europe, it is straightforward because only the EU organic logo, the green leaf, that really counts.

Sometimes, Ecocert is said to be a certification. It is not. It is a control agency (one of many) that issues certificates on behalf of the EU. Which control agency the producer uses is irrelevant for the consumer. All follow the same rules.

Biodynamic certifications, such as Demeter and Biodyvin, are not organic certifications per se. They are private biodynamic labels (we’ll come back to what biodynamics is in a later article). They do require that their members are certified organically by the EU, but they also have other rules that are quite different from the organic rules.

So, to clarify things further:

- There is only one organic certification (within the EU) and it is the one illustrated by the EU leaf

- Each country has a number of control bodies that certify that the producers follow the EU rules

- If you want to indicate that you are organic you must use the EU leaf

- You can also put on the label the name and logo of the certifying body (Ecocert, Bioagricert etc), as well as agriculture biologique, “organic wine” or similar, but that means nothing more than the EU leaf

USA

The United States also has official rules for organic wines. The EU and the US differ in one crucial respect. Organic wine in the USA cannot contain any added sulphur.

Under the National Organic Program, NOP, which comes under the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), there are two levels:

“Organic wine”, which is made from 100% organically grown grapes. Yeast and any other additives must be organic. It is forbidden to add sulphur dioxide during vinification. There may be some natural sulphur in the wine of course, but nothing added. For this category, you can put “organic wine” on the label and also the USDA logo. Organic wine is unusual in the United States because of the strict rule about sulphur. Few producers dare to risk working like that.

Most producers instead opts for the second level, which is “wine made with organic grapes“. Here too, you must use 100% organically grown grapes. But you are allowed to add sulphur dioxide, a maximum of 100 milligrams per litre, which is a little less than the EU rules. The USA has chosen to have the same permitted amount of sulphur for all types of wines, while the EU distinguishes between white, red and sweet wines. For this category, you put “made with organic grapes” on the label. (Within the EU the denomination “made with organically grown grapes” is not allowed since 2012.)

Import of organic wine to the EU

The EU and several third countries have recognised each other’s organic rules and control systems as “equivalent”. The list includes Argentina, Chile, USA, New Zealand, Canada and Australia. So, when these countries’ organic wines are imported into the EU, they don’t need to be inspected again by an EU control agency.

The EU leaf may be put on the label, and many third-country producers do so to make it easier for EU consumers to understand that their wine is organic according to EU rules.

This means, of course, that regulations in many third-country rules follow the EU rules.

No certification, why?

It is a good thing that more and more people choose to have a certification. More research is needed to develop effective, environmentally friendly products. And the more people who show that they are organic, the stronger the group becomes.

But of course, there are also those who in principle, are against certification. Those who say that why should we, the environmentally friendly, have to pay to prove it?

There are also some producers, as we noted in the article on organic viticulture (Part 2), who consider that the organic rules are not so good and therefore chose not to be organic.

Some say that they work most of the time organically but prefer not to be certified because they want to have the possibility to spray synthetically if the weather becomes difficult. Such an attitude is not compatible with organic thinking. They probably work well, but they work sustainably, not organically. In such a case, to call oneself organic or “almost organic” is to deceive the consumer.

Note: Most other certifications (not “organic”), for example for biodynamic or natural wines, are private ones and can exist in several different versions, and are not “official” in the way an organic certification is.

Don’t miss the other articles in this series on organics, biodynamics, sustainable, and natural wines. See the list at the beginning of this article.

If you want to know more about this subject you can read our book “Biodynamic, Organic and Natural Winemaking”.