What is natural wine? Are there rules? Is it good or weird? The concept of natural wine has emerged in recent years. It has been covered in media and bated. Many people have never drunk a natural wine and wonder what it really is. What does it mean that a wine is “natural”? Is it even possible? We explain what natural wine is, what the advantages are and which are the challenges.

I remember one of my first visits to a natural wine bar. It was in Paris and the year was 2009. The owner stated proudly that none of his wines had been clarified, filtered, sulphured or oaked. I tasted two wines that evening. One was cloudy and probably refermenting, the other was oxidised.

This is an article in our eight-part series. Here’s the full series of articles on organic, biodynamic, natural and sustainable:

- Organic, biodynamic and sustainable wine, an overview | part 1

- Organic viticulture: What is it really? | part 2

- Organic wine: in the wine cellar | part 3

- Organic certification | part 4

- Biodynamics: What is it really about? | part 5

- Natural wines | part 6

- Sustainable wines | part 7

- The future of organic wines | part 8

- Bonus: Video master class on organic wine

Since then, I have been to countless natural wine bars. The wines are still at times a bit hazy and oxidised. Sometimes they are excellent, sometimes they are awful. Part of the charm, perhaps?

In 2009, natural wines was a relatively new phenomenon for most wine drinkers. But it had already become trendy to drink them in some wine bars in Paris, Stockholm, New York and London. The 3-star restaurant Noma in Copenhagen served nothing else. Natural wine shops were popping up like mushrooms after a rain in Paris.

Natural wine is a niche. But a niche that gets a lot of attention. What is it all about? It is not entirely obvious. There is no official definition as there is for organic wine.

It started slowly in Beaujolais in the 1980s when growers such as Marcel Pierre and Jean Foillard began making wine without additives. It spread in France. Not least the Loire Valley became a stronghold, and then it continued out into the world. Soon the wines were called natural wines.

Simply put, natural wine is supposed to be made without the help of additives and technology in the cellar. But it is not quite as simple as that, as we will see later in the text.

Natural wine and unnatural wine?

The very expression “natural wine” is in itself provocative. We definitely don’t like it. It suggests that other wines are unnatural. All wines are a product of man and not something that creates itself. But the word natural wine is now so well established that we have to live with it.

From a marketing point of view, it was a stroke of genius to call it natural wine. Who does not prefer wines that are “natural”? And who wants wines that are unnatural? The situation is exacerbated by the fact that many natural wine advocates paint a picture of all wines that are not “natural” (in the way they want them) as “industrial wines” or something similarly unpleasant. A more honest description might have been “minimal intervention”, or “raw wines” (raw in the sense of unprocessed, as “brut” in champagne) or something like that.

In France, you are not allowed to say “vin nature” on the label. So, when a private label for natural wines appeared earlier this year, the French authorities did not accept that wording but instead “Vin méthode nature” was deemed OK. An important distinction. The method of production could be called natural but not the wine. (Read more on vin méthode nature here: “Vin méthode nature”, a new (private) French label for “natural wines”. )

There are several other groups or associations of producers of natural wine, similar to “vin méthode natur”, so they are not unique. For example, VinNatur in Italy. Read our article on VinNatur: Will new rules make “natural wines” more normal?

Some enthusiastic supporters of natural wines don’t drink anything else. Others are so sceptical that they run for cover as soon as they hear the word.

The best thing is not to belong to either of these two groups. The latter group misses out on some exciting wines. Whatever you may think, it’s always interesting to broaden one’s horizons. And for the first group, where do they draw the line? Because as you will soon see, there are degrees in naturalness. It is not self-evident what is “natural” and what is not, and it is not necessarily always good.

No additives, except…

If the ruling principle for natural wine is “no additives and no technology“, it is stretching the truth.

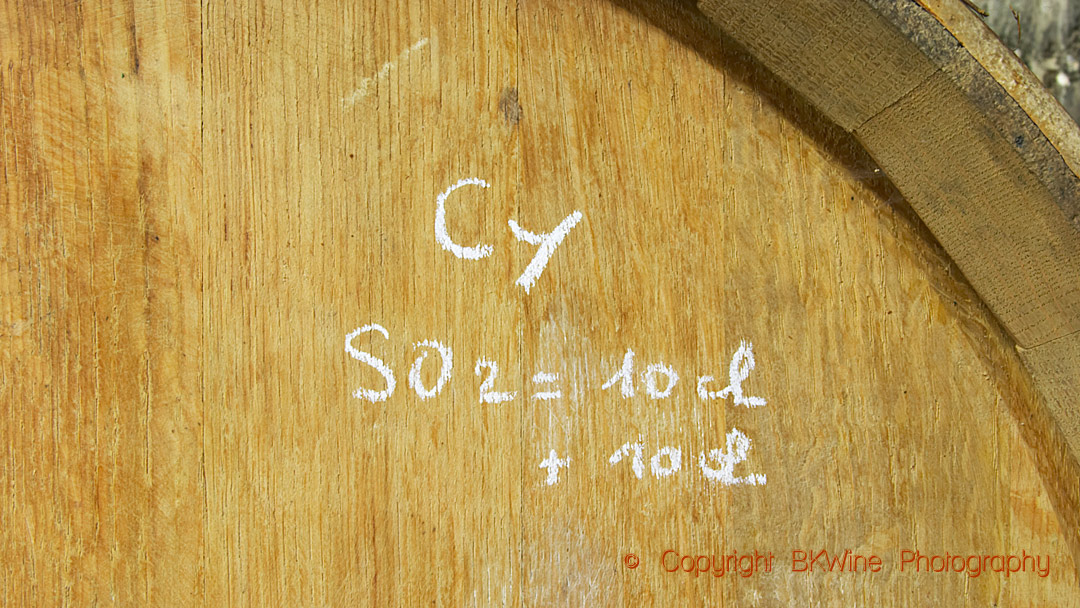

Even natural wine producers sometimes add sulphur dioxide to stabilise their wines. Very few do without. In the natural wine circles, it is usually considered acceptable to have around 30-50 milligrams per litre in the wine.

VinNatur, a very ambitious Italian private label for natural wine, states in its rules that a white, rosé and sparkling wine may have a maximum of 50 milligrams per litre of sulphur dioxide at the time of bottling and a red wine a maximum of 30 milligrams per litre. This includes the sulphur dioxide that is naturally released by the fermentation. The rules also state that the members must continuously work towards the goal of doing away with added sulphur entirely.

Members of the newly created Vin Méthode Nature can have up to 30 milligrams/l of sulphur (added + natural), but they need to mention it on the label, and they can only add sulphur at bottling, so after the vinification.

These limits are much lower than for both organic and conventional producers. And they can, of course, add sulphur at any time before, during or after the vinification process, which is safer. Adding sulphur at bottling can make the difference between good and bad natural wine, but there is a risk that the damage is already done before it is time for bottling.

For these two associations, the members must be organically certified, harvest manually and ferment only with the natural yeast. No other additives are allowed, except the sulphur as mentioned. So they cannot, for example, use clarification or filtering aids, nor correct the acidity. “Brutal” or “unnecessary” techniques must not be used during the vinification (not entirely clear what this means). However, temperature control during fermentation is allowed. VinNatur also allows a light filtration and its members can use carbon dioxide, nitrogen or argon gas to protect the wine from oxidation.

However, most natural wine producers do not belong to an association, and thus they have no specific set of rules to follow. Sometimes they are certified organic, sometimes not. Working organically should however be a matter of course for someone who claims to make natural wine. Maybe they follow similar rules in the cellar as the above associations, or perhaps they have their own rules.

In the end, it is a question of how much the wine consumer trusts the word of the producer on what he does, and also a question of how much information the consumer has been given. In practice, it can be hard to know what the situation is for many natural wines.

Sulphur is there for a reason

The debate about natural wine has, in many ways, been about sulphur and yeast.

There are good reasons to use sulphur dioxide during the vinification. It protects against acetobacter and thus prevents the wine from becoming vinegar. It is an antioxidant. It protects against Brettanomyces, a yeast fungus that can produce unpleasant off flavours, and other microorganisms present in the juice and the wine which can cause defects.

The risks you run by working without sulphur (or with very little) are thus that you can suffer from taste problems and hygienic problems. You can get off-flavours or unstable wines that can suffer from post-bottling fermentation, acetobacter or other. It does not have to be so, but it happens more easily, which is the reason for the strange flavours of some natural wines. Too much volatile acidity, i.e. a hint of vinegar, is a common problem (volatile acidity in small amounts is not in itself negative, but can contribute to character and complexity).

Sulphur also protects against oxidation. Oxidation is a natural development as the wine ages and contributes, among other things, to the maturity characters of wine. Without sulphur, the wine can oxidise faster, which can lead to the wine tasting “old” already when young.

The “natural” yeast

The natural winemaker must also refrain from adding cultured yeast. Selecting and adding a specific yeast is otherwise a useful tool if you want to refrain from adding sulphur. One way to protect your must and wine from harmful microorganisms is to ensure that the fermentation starts quickly and goes on until all sugar is gone. By adding cultured yeast (sometimes called “industrial yeast”), the winemaker has better control of the fermentation and knows that the yeast will be able to finish the job. The wild yeast is not as reliable. Still, many producers we know are very happy with the natural yeast (sometimes called “wild yeast” or “indigenous yeast”), and it seldom causes them any problem. But we also know many who would never dare rely on it.

(More on yeast (follow the link for our yeast articles): “natural” yeast is the yeast that is found on the grapes and in the wine cellar. No yeast is added; instead, one relies on that there is “sufficient amounts” of yeast in the “environment.” There are, however, a wide variety of yeasts, some good others not so. The “cultured” yeast (industrial yeast) is not artificial. It is simply a selected variety from naturally occurring yeast, which is then propagated on a large scale. There are a plethora of different cultured yeasts to choose from, with different characteristics. Read a winemaker’s view of yeast in our article: “Using native yeast or selected yeast at Quevedo Wines in the Douro”.)

Does it make a big difference to the wine if you use the wild yeast? It does, says Angiolino Maule in Gambellara, the founder of VinNatur. For him, the natural yeast makes every winery unique. If it brings more terroir character to the wine, we don’t know. Others say that if you have ever used cultured yeast for some reason, then that will be the predominant yeast in the cellar and will be the (main) one to do the fermentation.

The natural winemaker must have total control of the process from harvesting to bottling to minimise risks. Excellent natural wine is not made with any laissez-faire method but with attention and control throughout the vinification.

But all natural wines are not excellent. On the contrary, they have a reputation for being peculiar (“funky”) and sometimes faulty. Is the rumour true? Partially, yes. But it all depends.

“No poisons or chemicals in the vineyard”?

Sometimes you hear the comment that natural wines are made “without spraying in the vineyard”. Do not believe it.

The wineries of natural wine producers also suffer from diseases, e.g. mildiou and oidium. So they also spray their vineyard. There may be a few exceptions, but, in practice, all natural wine producers use sulfur and copper (a heavy metal), or sometimes other products, to protect their vines against disease.

How do natural wines taste?

Having tasted and drunk natural wines for over ten years, I have concluded that the taste is less about the absence of additives in the wine and more about the wine producers’ philosophy. What kind of natural wine do they want to make?

Are they rebels who want to be outside all appellation rules? Their way of working often results in wines that are not “typical” for their appellation. Their wines are often the juicy, refreshing and easy-drinking style of natural wine, pleasant, although they sometimes taste more like cider than wine (which can be due to volatile acidity). They can be a bit fizzy (can be due to post-bottling fermentation). In France, they are often sold as vin de france, i.e. wine without any specific origin. The rebels like colourful and playful labels with imaginative names, so taking a look at the label can give you a good hunch of that it is “natural”.

Or do they want to make wine within the framework of their appellation? For the members of VinNatur, the aim is to make “normal” wines, wines that fit with the classic ideas of appellations, but in a natural way. Many of these wines would therefore be rejected by the hard-core natural wine enthusiasts simply because they taste like a “normal” wine. VinNatur does not tolerate defects or off-flavours.

For some consumers, a natural wine shouldn’t be “normal”. If it is, they will be disappointed.

Some growers can make wine without additives and other tools. But apparently, it is not easy. Some natural wines feel dull, with a dried-out fruit and a short finish. Some are oxidised. Sometimes the volatile acidity is way too dominant. Occasionally an excessive “farmyard” (Brettanomyces?) aroma makes the wine feel defective.

But at times the wines are excellent with lovely fruit. And we often like white wine with a bit of oxidation. A slightly higher volatile acidity does not have to be negative either. If it is not exaggerated, it will give a personal style to the wine.

Are natural wines the ultimate expression of “terroir” and origin?

Very often, it is difficult to say where a natural wine comes from. We drink a lot of natural wines at home, and we always taste them blind. We can usually recognise that it is a “natural” wine but can rarely identify neither region nor grape. Some producers agree with us and acknowledge that this is a problem.

It does not have to be considered a problem if the wine is good. But claiming, as natural wine enthusiasts often do, that natural wines are the wines that best express their terroir, origin and grape is for us incomprehensible. For us, it is quite the other way around. It is a bit ironic that a natural wine thus becomes a “technical wine”. The first thing that you notice when you taste it blind is the technique (or lack thereof) that the producer uses. Origin and grape variety are obscured by the production methodology.

Natural wines can be excellent, whether they are made in a classic style or show new and unusual taste sensations. But if you think a wine is defective, it probably is. Some natural wines are appreciated only by the truly devoted. A bit like old Danish cheese or Asian fermented fish sauce.

For the consumer, it is always a bit of a gamble. Buying and drinking a natural wine can be exciting and give you new taste experiences, but it can also lead to disappointments.

Where and how to find natural wine?

It is not always easy to recognise a natural wine when you are in the shop looking for one. The playful label I mentioned above is a clue but by no means waterproof. Natural wines tend to come from less prestigious regions. In France they often (but far from always) come from the Loire Valley, Beaujolais, Languedoc, the Southwest. However, this may perhaps not be of much help if they are sold as vin de france, without a specified origin. A sparkling wine with a crown cap is most certainly a natural wine. Orange wines are sometimes natural wines but not always. (To be clear, orange wine is in no way synonymous with natural wine.)

I recommend that you ask in your wine shop or try them in a natural wine bar if you have one in your neighbourhood. The wine bars are run by passionate people who can explain the wines. Don’t be surprised if you don’t recognise any of the producers of the wines in the bar. We usually don’t. Some natural winemakers have an international reputation, for instance, the pioneers in Beaujolais, but many more are small and not very well-known. One of the charms with natural wines is to try something unknown.

Is this how they used to make wine?

Wine has never been “natural” in the way that some natural wine enthusiasts want us to believe. There is far too much nostalgia about “the olden times”.

“Natural wine is the old way of making wine, the way it always used to be made” is something we often hear. I wonder. There’s not much truth in that. Rather, it is a myth.

Sulphur is nothing new. It has been added to wine for 500 years, perhaps longer. Additives are not a new innovation either. The Greeks and Romans added plenty of things to their wine, seawater, honey, spices, algae, milk, saffron. At all times, winegrowers have used “tricks” to make their wines taste better, look better and keep longer.

Compared to wine growers of times long passed, however, today’s natural wine producers have a significant advantage. They know about the microbiology of wine. They know how to manage their vineyard to get the best grapes. Not least, they have access to temperature control.

There are a few natural wine producers who do not use temperature control at all. That would be an even greater challenge. But even that can probably work if you use very small tanks. Or amphorae, inspired by the old Georgian (the country) tradition of burying clay jars called qvevri. It has become popular in natural wine circles to ferment and age in amphorae or other kinds of earthenware jars. However, not all amphorae wines are natural wines.

Wine without sulphur is not always natural wine

As sulphur has become an important topic of discussion, a new category of wine has emerged. It is wine with no added sulphur without it being a natural wine (although that, of course, depends on what definition you chose to use).

Today there is a market for “normal” wines without added sulphur. Large wine companies have realised this. Sulphur is an allergen that some consumers want to avoid even though very few people are so sensitive to it that they would get an allergic reaction by drinking wine with sulphur.

If you make large volumes of wine without added sulphur dioxide to be sold in supermarkets, you use other additives or technologies in the cellar to obtain a stable wine. These wines are often certified organic but not always. The important thing here is the absence of sulphur. Some wineries also make sure that they choose cultured yeast that releases as little natural sulphur as possible.

Wine “without added sulphur” is not always without sulphur

Much of the discussion about natural wines is about sulphur, and above all about “added sulphur”. However, one should remember that sulphur is released naturally during fermentation and is therefore naturally present in the wine.

In other words, a wine “without added sulphur” most likely still contains sulphur.

On virtually all wine bottles, we see the warning text “contains sulphites”. If the wine contains more than 10 mg of sulphur dioxide per litre, the warning text is compulsory on the label. It is difficult to get below this limit. As an example: The above-mentioned “Vin méthode nature” has two symbols. If you have added sulphur dioxide, it says “Sulfites <30mg/l”, where the figure refers to how much sulphur is left in the wine when bottling (not how much is added). If no sulphur dioxide has been added, the wine may contain a maximum of 20 mg/l natural sulphur dioxide according to their rules. However, this does not need to be stated on the label, according to their rules. But you have to have the usual warning text anyway.

So the fermentation itself can give not insignificant amounts of sulphites in the wine.

Do we need an official certification for natural wine?

As we mentioned above, there are several different organisations that “certify” natural wine, i.e. allows members to put out a logo on the label if they follow the rules. “Vin méthode nature” and VinNatur are two, but also, e.g., Association des Vins Naturel (AVN), ”Les Vins S.A.I.N.S. ’Sans Aucun Intrant Ni Sulfite’ (ajouté)” and others. (And to avoid any misunderstanding: Vin méthode nature is not an official French designation.)

There is no official or generally accepted definition of what natural wine is, beyond what we have explained above. Is it needed?

We do not think it is needed, just as we do not need an official certification or definition of what orange wine is, or “old vines”. Natural wine is one of these concepts that most people have a vague idea of what it means and the details are then a matter of what each wine producer chooses to do, and what each wine consumer is looking for.

Besides, creating an official definition goes against the rebellious spirit that drives many of the producers.

For us, the somewhat vague situation that exists today is enough. Everything does not have to be precisely defined.

The future of natural wines

Natural wines are an exciting addition to the wine world. The negative side of it is the propaganda that some of its proponents paint pretending that wines that are not natural are soaked in dangerous chemicals made in nasty factories. That is not true, of course. But many people know nothing about winemaking, and they might believe it.

Can big wineries make natural wine? I don’t see why not. It is a question of working rigorously. VinNatur in Italy however, says that “natural wine is produced in small rather than industrial quantities by an independent producer”. But that is their point of view. Anyhow, it is hard to imagine big wine producers refraining from most of the techniques that today are available in the wine cellar, especially for inexpensive wines, not least given the significant risks they would run when producing large volumes of wine.

Natural wine will continue to be a small niche. But at the same time, I think the concept will broaden. Maybe we will have more wines without added sulphur and no other additives except something “natural” to stabilise the wine. It is already possible, and more research is underway. These wines should be natural enough to fall into the category of natural wine. The definition of natural wine will probably become (even) more blurred over time.

The trend is definitely moving towards less interference, for many wines, not least the organic and biodynamic ones. Certified biodynamic growers have rules that allow very few additives. As always, it’s about learning which growers you like.

Don’t miss the other articles in this series on organics, biodynamics, sustainable, and natural wines. See the list at the beginning of this article.

If you want to know more about this subject you can read our book “Biodynamic, Organic and Natural Winemaking”.