Is VeriVin SWA001 the Holy Grail to fight wine fraud?

Wine fraud can be of the spectacular kind of selling fake Romanée-Conti, or it can be of a more mundane type, selling bulk wine that is not what it pretends to be. In both cases, there can be a lot of money at stake. There are two big difficulties with fighting wine fraud. First, the wine is often in a closed container (a bottle) that can’t be opened and sampled. Second, wine is such a complex liquid, so it is difficult to make an accurate analysis. VeriVin is a new technology developed by an Oxford start-up that might solve these problems with counterfeit wines. I talked with the founder of VeriVin, Cecilia Muldoon.

Rudy Kurniawan, Hardy Rodenstock, The White Club are only some of the most famous ones. Many more names have this thing in common. They bring to mind wine fraud. Fake wine. Counterfeits. Ridiculously expensive bottles that are not quite what they pretend to be come to mind when thinking of wine fraud. A bottle of Yquem from 1784 found behind a brick wall in a Paris cellar. A rare Clos St. Denis from the exclusive Domaine Ponsot in Burgundy sold at auction in New York, but from a vintage when the domain didn’t make any wine. Romanée Conti from Domaine de la Romanée Conti, the world’s most expensive wine, in a bottle with a torn label, with curiously the exact same tear on the label at more than one tasting.

A shorter version of this article has been published on Forbes.com.

But, in fact, this is just the most spectacular type of wine fraud. It also happens at the other end of the scale, really cheap wine. For example, the French wine merchant who sold the equivalent of 18 million bottles of pinot noir to an American winery to go into a cheap wine blended in the US. The issue: there was not that much pinot noir made in the whole of the region, and, in fact, it was a blend of cabernet and merlot.

The challenge is, of course, that it is terribly difficult to authenticate a wine accurately. It is particularly complicated when it comes to rare bottles, the ones that are sold at auction or through highly specialised wine merchants for thousands or tens of thousands of dollars. You really don’t want to open that rare bottle and take a sample to put it through a machine to analyse it, for example, through a gas chromatography analysis. That will, in effect, destroy all value of the item you want to authenticate.

But it can be almost as challenging to make sure that pinot is pinot or that the wine comes from the wine regions it purports to come from. There is currently no fool-proof way to identify, for example, a grape variety or an origin.

At the same time, huge amounts of money can be at stake. Counterfeits can make millions of dollars land in the wrong hands.

How big a problem this is, is difficult to know. People subject to wine fraud or fake wine scams tend to be reluctant to publicise it. But we can be pretty confident that counterfeiting is a bigger problem than what is illustrated by the few well-known cases.

What you want is a non-intrusive and non-destructive analysis – i.e. something that does not affect the contents nor require you to take a sample – and that accurately identifies what’s in the bottle. The problem is, of course, lesser when it comes to wine that is not in bottle, for example, bulk wine samples, since sampling is not then an issue, but the speed and accuracy of the analysis is still crucial.

A new technology, currently in development by a UK-based start-up called VeriVin, may be about to solve this conundrum.

VeriVin hopes soon to have a solution that will accurately verify that a wine is what it claims to be based on two different technologies.

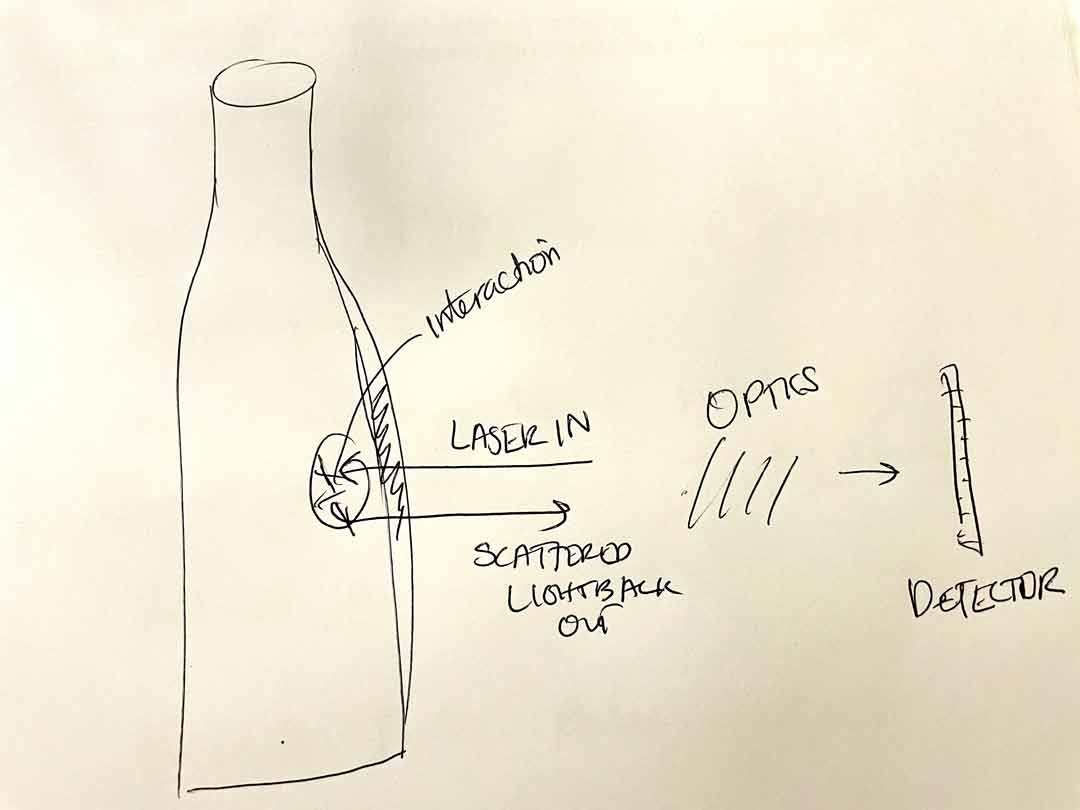

The first part of their solution is a sort of “optical scanner”, or to be more specific, a spectroscopy machine based on the Raman scattering effect.

The name comes from CV Raman. He was an Indian physicist who discovered the effect in 1928 and described it in a paper called “The Molecular Diffraction of Light”. In 1930 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for his physics research.

This is how it works:

You shine a light into the bottle. Some of it is “reflected” back by the liquid in the bottle. You then analyse what the light looks at when it comes out of the bottle.

Simple! Not really.

First, the light has to be very specific and controlled. For this, they use a laser. When the light passes through the wine, it “changes” due to the Raman effect. The light passing through the wine interacts with the electrons in the wine’s molecules. This causes minute changes in the energy in the light and its direction. What kind of changes happen depends on what is in the bottle. The light “scatters” due to the interaction between the electrons in the wine’s molecules and the light photons. How it scatters depends on the exact constituents of the wine. You can compare it to how a prism creates a rainbow of the light that passes through it (although scientifically it is not the same thing).

So, by analysing the light that comes out of the bottle, what changes have taken place, you can determine with some accuracy what is inside the bottle. In a way, you could say that the light that comes out of the bottle gives a kind of “fingerprint” of what’s inside. VeriVin also calls it the wine’s “signature”.

What makes this a bit more complicated is that the light has to pass through two walls of glass, the bottle, on its way from the laser to the sensor. In and out of the bottle. If it was all in a laboratory context, you could precisely control what glass it is, but if you are handed any old bottle of wine, then you really don’t know much about what kind of glass it is. To make VeriVin work, they must “subtract” the effect of the glass from the analysis. This, I am guessing, must be one of the big challenges in the solution.

So, let’s say you solve all that. Now you have a fingerprint of the wine. How can you exactly tell what it is? That’s the other part of the solution.

VeriVin plans to solve this by building a database of information from thousands of samples against which any new wine bottle analysis can be compared. A mix of machine learning and artificial intelligence. The more bottles and wines that they analyse, the more accurate the result becomes. With time they hope to be able to accurately determine, for example, from where a wine comes and maybe even exactly what wine it is.

But I must admit that even though I have a physics degree, I did not understand all the exact details of the explanation when I talked to Cecilia Muldoon recently on a web call to get an understanding of what they do. Cecilia is the founder and CEO of VeriVin. She has a PhD in experimental atomic and laser physics from Oxford University, and, no surprise, when she was at Oxford, she was the captain of the Oxford wine tasting team. (No, I don’t know if they won against Cambridge that year.) She started VeriVin in 2018, five years after graduation from Oxford, and now has a team of some eight working full-time or part-time on the project.

“We have three more months of development before it is finished,” said Cecilia, “fine wine merchants is one of the first types of users that we see.” But she also pointed out that it can be very relevant for merchants of bulk wine or other volume wines who want to verify that what they have had delivered from the supplier actually corresponds to the samples on which they made purchasing decisions.

As the technology with time is used more and more, the accuracy of the analysis will improve. “The more samples we have processed, the better we can analyse the results from the spectroscopic analysis. All the results will be stored in our database and contribute to improved precision.” This is, of course, something that may be an issue for some potential users – that the data is collected and stored – but Cecilia is keen to point out that the data is totally secure and private and used only for improvement of the results. I imagine that it is something that will be made clear in any user agreements.

The VeriVin machine is the size of a large brief-case, and goes under the name SWA001. On one side, you have a compartment that you can open and insert a bottle. You then close the door, press the button, and the machine does its magic.

So how can a winery or a merchant get access to VeriVin? “We are planning a rental model with a subscription,” says Cecilia, “and perhaps also to provide it as a service.” Another possibility might be to buy a VeriVin machine from them. Cecilia was, understandably, reluctant to mention a price officially but did let slip a number that was several times more affordable than other devices based on similar technology, and that don’t even analyse wine… The technology is already used, with similar devices, to analyse various materials, liquids, gases and solids, as well as for several scientific applications.

For the future, they also have plans to extend the applications of the technology to use it on other liquids. Whisky and other spirits, olive oil, honey, health care and others.

They are now in the final phase of development with maybe only months until official launch. They are also actively looking for pilot customers, or what they call development partners, so if you think this sounds like an exciting tool and you are willing to give it a try, then now might be the perfect moment to contact them. Their website: https://www.verivin.com/

If VeriVin works as it is hoped it will certainly help cast a bright light on some dark corners of the wine industry and remove the sour taste on many investors’ palates.