Taste is by definition subjective, but that should not hinder us from using a more objective approach when discussing wine and winnings.

What we tend to like varies. Some prefer to drink wine with a lot of maturation tones, others to drink wine young. And in addition, there is a whole spectrum of taste preferences that run in every possible direction. A neutral score sheet for how a “good wine” should taste does not exist and what is considered extraordinary today by wine critics and other stakeholders may well be looked upon quite differently in the future, depending on trends and changing perceptions.

In the wine world, the ageing potential of wine is widely discussed and how to assess its ageing capacity. But what is actually meant? There are, of course, no complete truths on the subject, but I thought I would describe how I personally think. If one agrees or not is up to each one.

Quality assessment of wine

Most people who evaluate the quality of wine from a more technical perspective use “BLIC” or similar evaluation methods. The abbreviation stands for balance, length, intensity and complexity and is probably the most used quality criteria for wine. In addition to these parameters, the acidity of the wine, sugar content, alcoholic strength and tannin structure are of great importance to how well the wine is able to age, but they are by themselves no quality parameters by definition.

Many also consider that “typicity” is an important quality marker, usually because the wine should reflect the grape composition and the region where the grapes were grown and that it represents the wine maker’s intentions. Not unlike how it works when you judge beauty or diving and such things.

The intensity gives an indication of the concentration, volume and extract of the wine, while the complexity reflects extent and width of the aromas and flavours of the wine.

The balance, which is the most subjective quality marker (where we generally find it hardest to agree, due to taste preference and physical sensitivity) is characterized by the fact that all parts of a wine should interact and gain space without the individual parts taking over and contributing with imbalance and disharmony. An unbalanced wine can also have a big impact on how complex the wine is perceived and how clearly more subtle elements appear and add flavour and aroma.

The length is a bit more difficult to describe, but many argue that it is about how persistent the taste is and how well it “fills the mouth in the long run”. I feel a little uncertain about this and probably tend to judge how persistent the taste is in its full form. A wine with a persistent bitterness, unripe tones and / or “fiery” alcohol should therefore not be interpreted as “good length” even if the sensation persists for several minutes.

The qualitative development and maturity of wine

A relatively large proportion of wine lovers live with the view that many quality wines should not be consumed young. Often with good reason, even though each person’s taste preference plays a big role. Wines that are made to be aged are generally found to be very astringent and rich in tannins in their youth. For example, think of a young nebbiolo from Barolo.

The tough structure and undeveloped character can therefore give an unbalanced impression where the structure of the wine, acid and in many cases unintegrated oak character and / or fruit obscures the impression of how pleasant the wine is to drink.

In its youth, the wine also lacks the nuances developed during ageing, so-called tertiary flavours, but consists only of the primary and secondary – ie grape-specific aromas of fruit and berries, as well as flavours derived from fermentation and winemaking. However, youthful freshness and brilliance should never be underestimated.

All wines develop tertiary maturation aromas over time regardless of the quality of the wine. Now it starts to become interesting. What is crucial is if the wine has sufficient staying power to be able to “carry its maturity” without losing too much fruit, texture and intensity. Maturation tones without any form of structural support are rarely a recipe for a particularly good or desirable wine. If all you want is maturity, then you might as well buy the simplest wine you can find and store it in a warm place for a year. If I you allow me to exaggerate just a bit.

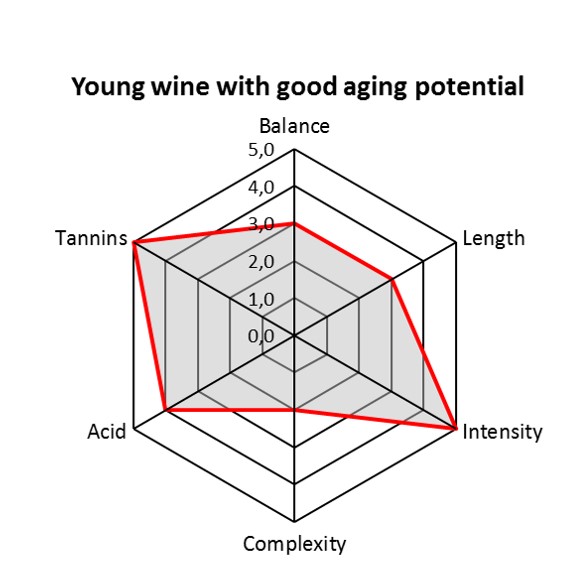

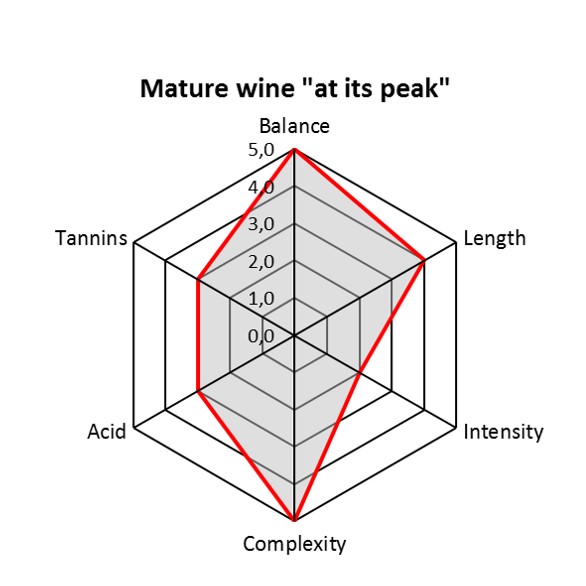

In the following two charts I have tried to visualize my view of how the BLIC changes on a young wine with ageing potential that, after adequate cellaring, blossoms into a hypothetically full-bodied wine:

Tannins tend to come smoother and fruit intensity decreases while complexity increases and in many cases the perception of “the whole” is more balanced and more “integrated”. In the example above, the total score on the scale has not increased but simply been redistributed. In many cases, we can probably assume that the totals can both increase and decrease due to the variety of the different characteristics and how he who tastes values the experience. As said before, but worth repeating, there is no truth or score sheet other than one’s own.

So, how do we decide if a wine is over the hill, too old, or alternatively, not worth ageing (in theory)?

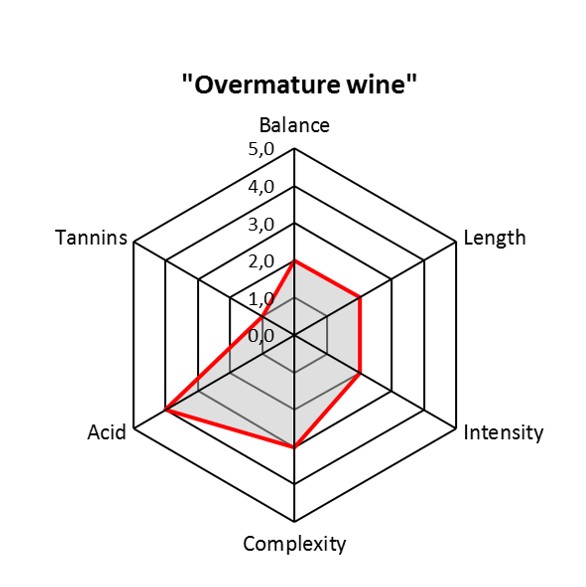

If the fruit and fundamental characteristics of the wine have disappeared and if the balance feels skewed and the wine has lost its structure, then I think technically that the wine is “dead”. If I like it regardless of its shortcomings, it’s justified to wonder if it would not have been even better in an earlier phase and perhaps I rather like it despite its shortcomings and not the opposite.

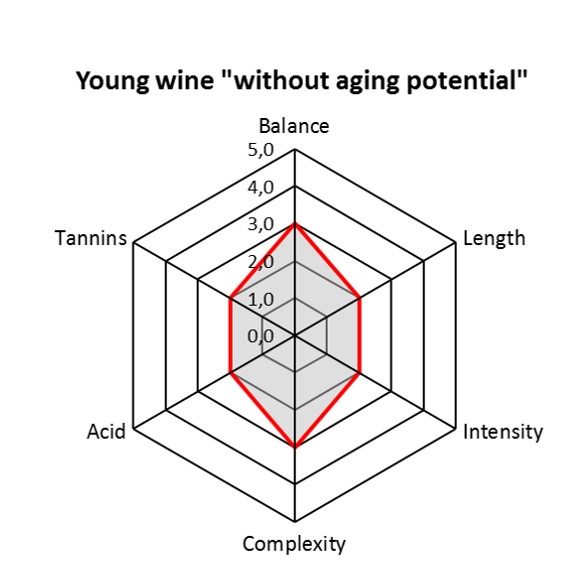

If a wine is aged for longer than it can handle, it also tends to lose complexity and risks being perceived as simply “generically” mature. One needs more than only a character maturation for a wine to be enjoyable, interesting and of good quality. A perfect wine in my world has both primary, secondary and tertiary aromas with good intensity, good length and high complexity. See the examples below on a wine that has clearly passed its optimal maturation phase, as well as a young wine with doubtful ageing potential, but that might still be quite good to drink young:

Final words

The advantages of using BLIC when assessing wine can be very significant while making it easy to understand and relevant. However, the aesthetic overall assessment is always the most important element. If you like something, you like it no matter what “points” the wine gets in a BLIC analysis, but it can increase understanding of why you like something more than something else and what qualities are important for assessing a wine’s quality and ageing capacity with a more objective approach. A way to put words to the experience and to convey the image to others. For example, in this case, the method works well to describe my view of how wine matures and why there may be good reasons to choose the right wine, with the right properties if you wish to cellar it and experience it in its maturation phase.

How do you experience a wine’s development from youth to perfect maturity? Write a comment!

Mattias Schyberg is guest writer on BKWine Magazine. He is also one of the persons behind the very active wine forum www.finewines.se.

One Response

Congrats Mattias. This article is perfect. I’ve been looking for an explanation about quality assessment and ageing potential for hours, then I finally found you article. Thank you for sharing your point of view on this issue, I totally agree with you.