Riesling is a magnificent grape but a difficult one. For its many devoted admirers, it is the foremost white wine grape in the world. Riesling is one of the most prestigious grapes, but it is still something of a niche variety. This is because it is a cool climate grape, limiting the number of countries it grows in. But it is perhaps even more because it is unpredictable; riesling is often a little bit sweet, or at least not completely dry, and it’s hard to know when. Here’s all you need to know to familiarise yourself with this wonderful grape.

Riesling is grown on around 55,000 hectares globally (the most planted white grape chardonnay has 210,000 hectares). As one would expect, Germany is the largest riesling country with just over 24,000 hectares. The grape was known in the Rheingau as early as the 15th century and came to Alsace not long after. It thrives in fairly cool climates. It buds late and thus avoids spring frost, and it can withstand cold winter temperatures. It is also quite a disease resistant grape variety.

What we perceive as tricky with riesling can also be seen as an asset. Residual sugar in a riesling ranges from 3 grams or less, i.e. completely dry, to 300 grams per litre and anything in between. It gives an incredible range of flavours. But it also means that it is not always obvious to know what is in the bottle that you are about to open. That’s what makes riesling a challenge, even for admiring consumers, like us.

This is a longer version of an article published on Forbes.com.

This is an article in our series of presentations of the world’s most popular and exciting grape varieties. Read other articles here:

Many riesling wines can be described as “not-totally-dry-wines”, meaning that they are slightly sweet. They have some residual sugar.

Riesling has very high acidity, higher than most other grapes. It is the acidity that makes riesling wines wonderfully fresh and delicious. But for the acidity to be balanced, many wine producers believe that some residual sugar is needed. Therefore, they stop the fermentation before all sugar has been transformed into alcohol. Sometimes, say some growers, the fermentation stops by itself before the yeast has consumed all the sugar. The sugar level can vary from one vintage to the next in a wine.

If the sugar level is around 6 grams, you don’t usually feel the sugar, or only slightly, due to the high acidity. But with 8-12 grams of sugar or even more, as is sometimes the case, it starts to get “problematic”. That is to say unless you are looking for that kind of wine. Many consumers are sensitive to high acidity and agree with producers that a little sugar is needed.

This is similar to the discussion around Champagne. Here too, the acidity is very high, and the producers believe that a little dosage, a small dose of sugar, is needed for balance. But for those who like a distinct acidity the sugar level can become too high. If you want brut nature champagne (without added sugar), a crisp riesling or something more sweetish is a matter of taste.

What does riesling taste like?

Riesling is an aromatic grape with a clear and often easily recognisable aroma. Citrus and flowers dominate, but you can also find green apples, pears, rhubarb and in a warmer climate, sometimes tropical fruits such as pineapple and mango. There are occasionally lovely honey notes even when the wine is completely dry, especially after a few years of ageing. It is usually relatively light in body.

The high acidity gives firmness or edginess to a very dry riesling, a style that you either like or dislike. A hint of petroleum sometimes appears after a few years’ of ageing. This aroma comes from an organic compound called TDN (or if you want to full name: 1,1,6-trimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene). I quite like it, but it is not to everybody’s taste. This petroleum character seems to occur more in wines that come from slate and more rarely from limestone soil. A rare concrete link between bedrock (“the soil”) and taste, as geologist Alex Maltman points out in his book “Vineyards, rocks, & soils.” But unfortunately, it is probably not that simple. TDN also depends on other things, such as cellar temperature and the level of UV radiation the grapes get in the vineyard.

You rarely age or ferment a riesling in small oak barrels. However, large, old, “neutral” oak barrels are used, both in Germany and in Alsace. But the general perception is that an oaky character would obscure the finesse and elegance of riesling. The malolactic fermentation is often stopped to keep the distinct aromatic character. Not always though and some growers let some tanks undergo the malolactic, and then they blend. Doing the “malo” softens the acidity and gives the wine a little bit more body and a rounder character.

In the glass, a riesling is often quite pale, with a light golden or even greenish tinge. It’s rarely intense in colour.

Good quality riesling wines age very well.

Germany, the premier riesling country

Just under a quarter of the German wine acreage is planted with riesling. Some of the most famous riesling wines come from the Mosel, a region specialising in wines that are light in body, with some residual sugar and low alcohol. They tend to be a bit too easy drinking, but the best ones are delicate and elegant. Rheingau is famous for its high-quality riesling, usually with a bit more body. Here, 80 % of the wines are dry.

However, it is the sweet dessert wines from riesling that are considered to be Germany’s greatest wines. The high acidity gives the sweet wines an exceptional freshness and lightness. Beerenauslese, Trockenbeerenauslese and Eiswein are rare and magnificent wines.

There is a long tradition in Germany of making semi-dry wines. In the 19th century and the early 20th century, the grapes were often harvested unripe, partly due to inadequate knowledge of how to work the vineyard. We can assume that the acidity, therefore, was even higher than today. A balanced riesling in the 19th century was considered to need 10-20 grams of residual sugar per litre, writes John Winthrop Haeger in his comprehensive book “Riesling Rediscovered” (recommended reading if you really want to go into depth on riesling).

The tradition of residual sugar lives on even though they presumably pick appropriately ripe grapes today. Many consumers like the sweetish style. In Germany, for example, Riesling Kabinett is very popular. These are wines that you can drink “at any time”, says the excellent producer Fritz Groebe in Rheinhessen. His Kabinett has 11.5% alcohol, 10.5 grams of sugar and just over 9 grams of acidity. An example of a semi-dry riesling at its best.

Having residual sugar in a riesling wine has (unfortunately?) spread to other countries. Riesling in the USA almost always has a marked sweetness. In New Zealand, they are often made in an off-dry style. Some residual sweetness in the wine makes it easier to drink. It is more common for unpretentious, inexpensive rieslings to have residual sweetness than more expensive riesling.

What about bone-dry riesling?

What about bone-dry riesling, do they exist? Yes, they do, and their number is increasing. Slowly but surely, more and more rieslings are dry, both in Germany and elsewhere. Thirty-five years ago, only 16% of German wines were dry. Now, this figure is approaching 50%. Some producers today make only dry riesling. This is good. Bone-dry riesling, especially from Germany, has a remarkable, unique, crunchiness and liveliness that is hard to imitate. In my opinion, a good quality riesling doesn’t need any residual sugar.

If you make riesling within the EU and want to print dry (trocken in Germany, sec in France) on the label, the wine can have a maximum of 4 grams of residual sugar, or up to 9 grams provided that the acidity is at most 2 grams lower than the sugar content. So if the wine has, for example, 9 grams of sugar and 7 or more grams of acidity, then it can be labelled as “dry” (the difference between acidity and sugar is 2 or less). Which is not at all unusual for a riesling, which is often at 6-9 grams of acidity per litre. This is a bit of a convoluted way of saying that if the acidity is very high, then you are allowed more sugar in a wine called “dry”.

So, buying a “dry” (trocken) riesling doesn’t solve all problems. If you don’t want the sugar to hide the exceptional acidity; if you want that crispiness that you get from a maximum of 3 grams of sugar, then you have to choose your riesling carefully. But it is worth the effort.

France, also a great riesling country

In France, Riesling is found only in Alsace. It cannot be grown in any other appellation, according to the rules. You can make a vin de france, i.e. a wine without geographical origin, from riesling, but then you are not allowed to put the name of the grape on the label (you are allowed to put the grape name on the label for other varieties). Alsace producers have no desire to see their prestige grape appear in other French wine regions and compete with their Alsace wines, and they have been very successful in the grape-protectionism lobbying.

Riesling came to Alsace in the late 15th century but wasn’t cultivated in earnest until the second half of the 19th century. Around 1960, riesling became the most planted grape in the region. It is now grown on 3,500 hectares out of 16,000 ha in Alsace.

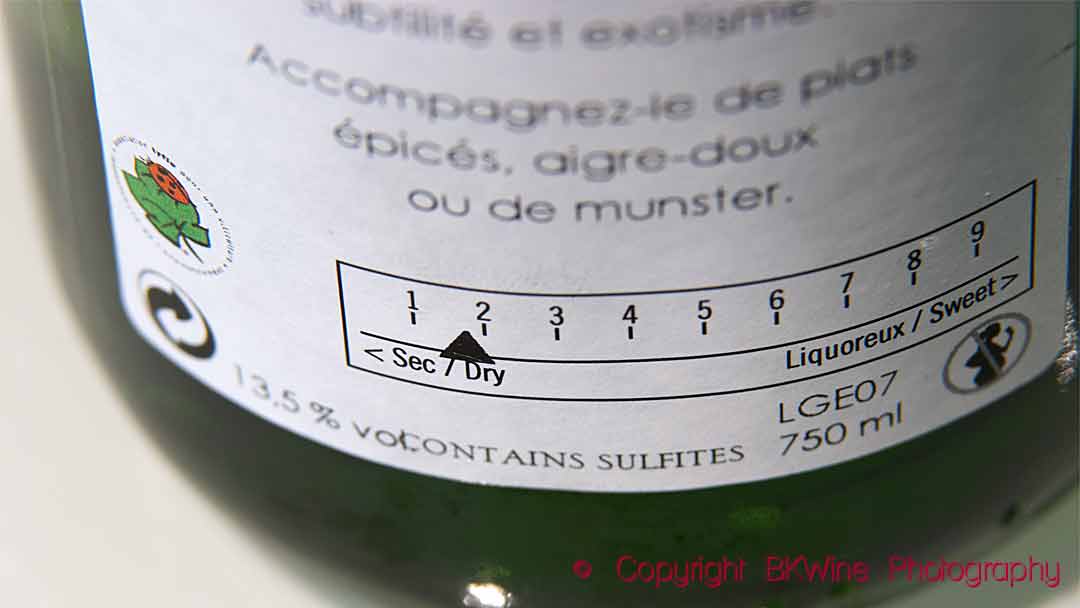

Alsace Riesling is often a bit more full-bodied than in Germany, but also here they can be both dry, semi-dry and sweet. You cannot always guess the residual sugar by looking at the label, but it is becoming more common to print “sec” if the wine is dry according to EU rules. Many Alsace riesling are dry today, especially from producers with high ambitions, although some inexpensive ones have 10-12 grams of residual sugar. Some producers have adopted a helpful “dryness scale” on the back label.

Riesling in other countries

California has increased its Riesling surface over the past ten years, from around 1,200 to 1,600 hectares.

The largest Riesling producer in the United States, however, is Washington, with approximately 2,500 hectares. Seattle-based Chateau Ste Michelle is said to be the largest riesling producer in the world. The residual sugar in their wines is typically 15-20 gram. They collaborate with the well-known Ernst Loosen from the Mosel region in Germany for the high-quality Eroica range.

In Australia, it is warmer and drier than in most other Riesling regions. In Clare Valley and Eden Valley, however, it is a bit cooler, and they make dry, crisp riesling. New Zealand has had great success with its riesling. I think we will see more of that in the future. Sometimes it is completely dry; sometimes there is residual sugar of 8-12 grams.

Austria’s riesling is a bit overshadowed by the country’s dominating grape, grüner veltliner. But the country makes some excellent riesling, almost always completely dry (3 g or less), in, i.e. Wachau, Kamptal and Kremstal, usually a bit more full-bodied than the German versions. There’s a total of around 2000 ha of riesling here.

Riesling facts

Acreage in the world: 55,000 hectares

Countries that riesling is mainly grown in:

- Germany 24,000 ha

- USA 5,000 ha

- France 3,500 ha

- Australia 3,000 ha

- Austria 2,000 ha

- Italy, Canada, New Zealand and others

Riesling’s character:

Elegant, high acidity, crunchy if completely dry, lemon, grapefruit, green apples, pears, sometimes honey that gives a little mouthfeel. Sometimes petroleum, especially after some ageing.

Synonyms: rhine riesling, johannisberg riesling, renski riesling, white riesling. However, italian riesling and welschriesling are synonyms for graševina, a completely different grape.

Don’t miss the other articles in our grape variety profile series. You can find the list at the beginning of the article.

This article was originally published in a shorter version on Forbes.com.