Are wine competition medals a useful buying indicator for consumers? Or are wine competitions a scam where producers buy medals to make their bottles look impressive? This article explains (in quite a lot of detail) what wine competitions are and how they work. I also describe why I think wine competitions are a helpful indicator of quality for consumers and why you can, in general, trust the medals as a “plus signal”. But not all wine competitions are equal. I discuss differences between how they are organised and the worth of their medals. All of this is based on my experience as a wine competition judge and taster for over twenty years on four continents. I also include a brief discussion on what quality is, and if you can evaluate quality objectively — or if it is always subjective, with a short note on “typicity”.

What is a wine competition? How does it work?

A wine competition is essentially a big tasting where wine producers have submitted wines to be tasted. The wines are tasted by an experienced tasting panel (tasters, sometimes called jurors or jury) and given scores. The best wines are given medals. Often, there are three different levels of medals: gold-silver-bronze, grand gold-gold-silver, or some other classification. Sometimes there are “super medals”, like best-in-show, best-of-category etc. It varies from competition to competition.

The wines are submitted by the producer. For each wine they submit, they pay a participation fee.

The medals are announced with fanfare and can be used as a marketing tool by the producers. They can be a purchasing guide to consumers. Medal stickers or neck collars are often pasted on the bottles.

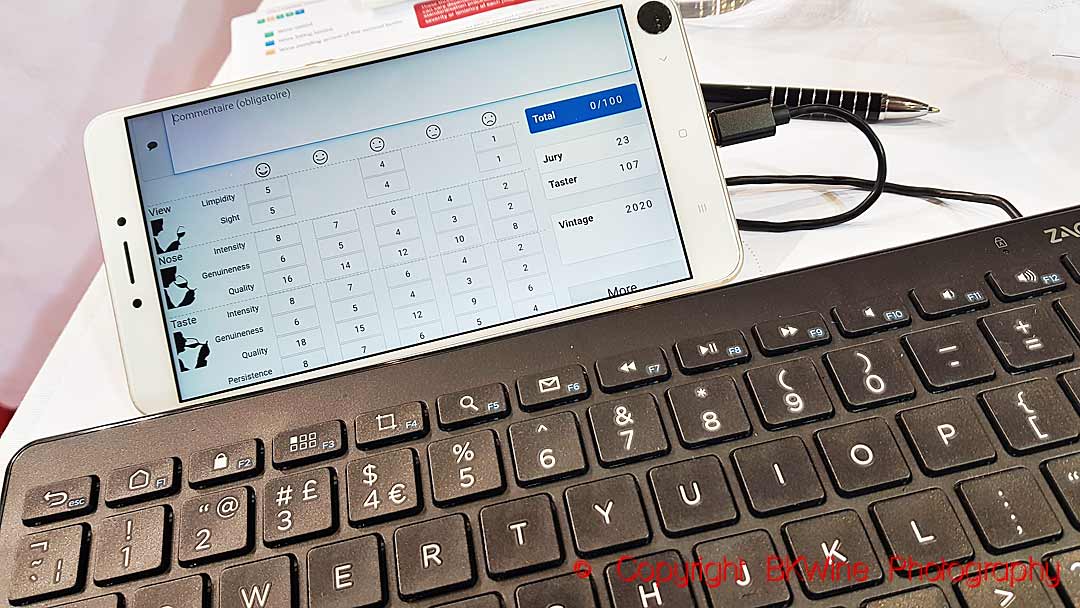

In some competitions, such as the Concours Mondial de Bruxelles CMB, the tasters are required to give a short written description of the wines in addition to the numerical score, which is then synthesised (using AI tools!) and given to the producer together with a graphical representation of the tasting comments.

I have participated in quite a few competitions in several different countries and of several different types. This article is based on my experience from these competitions. The one I most frequently participate in is the “CMB” (Concours Mondial de Bruxelles) that exists in several different versions: red and white wine, sparkling wine, sauvignon blanc wines, rosé wines, Chilean wines, sweet and fortified wines and some more. (The “Bruxelles” part of the name is historic; today, the only link to the Belgian capital is that their office is there, but the competitions take place elsewhere.)

This type of flavour chart or flavour profile is one of the feedback given to the producers at the CMB Concours Mondial. They also get a synthesis in words of what the tasters have commented:

I’ve also done many other competitions, Grenaches du Monde, Concours Amphore (organic wines), Apulia Best Wine, Rendez-vous du Chenin, The Silk Road Wine Competition (Silk Road Competition, China), Michelangelo International Wine & Spirits Awards (MIWA, South Africa), VinCE (Hungary), Challenge Entre-deux-Mers, Citadelles du Vin and many more. (More on our participation in competitions here.)

There is an abundance of wine competitions around the world. Here are some of the others that are well-known (I have not had the possibility to participate in either of these):

- International Wine Challenge (IWC), UK

- Mundus Vini, Germany

- Decanter World Wine Awards (DWWA), UK

- Balkans International Wine Competition

- Vinalies, France (for oenologists)

- Vinordic Wine Challenge, Sweden (being Swedish, I have to mention it, don’t I? Although it is very regional.)

- And many more

Many competitions focus on a specific grape variety: syrah, chardonnay, sauvignon blanc, vranec/vranac etc., sometimes with the (dubious) claim to select “the world’s best”.

We, BKWine, have also once organised a wine competition: The Scandinavian Wine Fair Competition in Paris in the early ‘00s.

What’s the purpose?

The primary purpose of a wine competition is to select and honour wines that are considered particularly good.

From a wine producer’s perspective, the purpose is, of course, to serve as a marketing tool. A wine with a medal may sell better. And maybe get recognition for a job well done.

The benefits to a consumer is that medals can guide you to good value or excellent quality wines or wine regions that you might not otherwise have discovered. It is a buying guide in a similar way that critics’ wine scores or tasting notes guide people to “better” quality wines.

Given that wine competitions generally are more or less blind tastings, they can be seen as more reliable buying guides than commentaries from wine critics who have tasted wines non-blind. If you are at Chateau Thisorthat or Domaine Grandvin and taste their wines, you are inevitably influenced by the environment and the people there. If you taste wine in elegant gilded salons of a Bordeaux chateau, the luxurious cadre and ambiance will influence your scores for the wines. No one, no matter how experienced, escapes that. Even if you taste the wines (in some way) “blind” in that kind of context, you’re biased. If you know what kind or category of wine you’re tasting, you’re biased in one way or another. Most wine competitions are not subject to the same bias, at least not those that are fully blind.

Another difference between competitions and wine critics’ individual scores is that in a wine competition the wine has been tasted and appreciated be several independent professionals with an acknowledged competence, not just by one single person (sometimes with an unknow competence).

In fact, looked at it this way, a commendation by a wine competition is more reliable and trustworthy than a tasting commentary or a score from an individual wine critic or wine journalist.

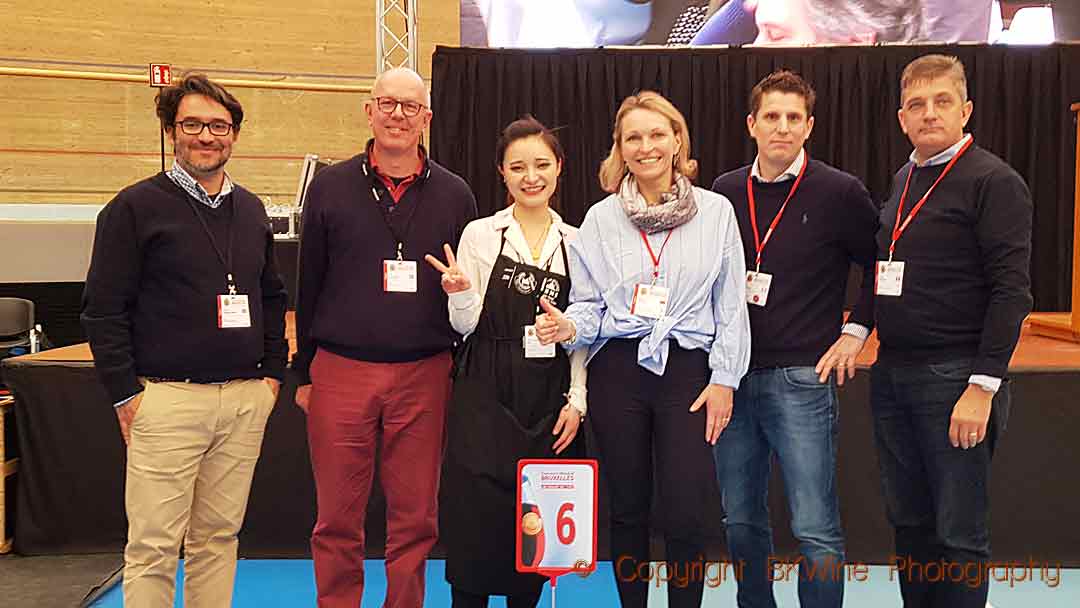

Here is “my” fabulous tasting jury in the Sparkling Selection by CMB in 2024:

Wine competitions also give lesser-known wine regions (as well as producers) the possibility to shine and be judged fairly. I once tasted a series of very impressive bordeaux style wines. The panel I was in scored the wines high. If we had known that it actually was a series of Chinese wines, I believe we would have been more reluctant to put such high scores. As I said, no one is free from bias or prejudice, no matter how experienced or professional you are. But again, this only works if you taste blind, not knowing what category of wines you are tasting. Not all competitions work like that.

From the organiser’s point of view, a competition is a business. They charge the producers a fee. The CMB charges up to €185 per sample. The Decanter World Wine Awards charges up to £170 + VAT. The International Wine Challenge charges up to £153 + VAT (2024). Grenaches du Monde, €120 + VAT, etc. Not an awful lot of money.

Some of these competitions have many thousands of participating wines, the CMB Red & White some 10,000, the Decanter DWWA 18,000, so it is a big organisation and complex logistics to put them in place.

Can you trust wine competitions? Do they help the consumers?

I used to be very sceptical about wine competitions, doubting that they added any value to consumers. After participating in a few, I changed my mind. I saw how it worked and the serious effort that was put into them by the tasters. Today, I do think they serve a purpose for consumers and that the medals can generally be trusted.

Wine competitions are not very different from wine scores (points) or reviews from individual wine tasters or critics (Parker, Suckling, Wine Spectator, BKWine Magazine etc). People use tasting scores (points) as a guide to if a wine is good or not. A buying guide.

Wine competition medals are very similar; they’re an indication of the “quality” of a wine. The main difference is that in a wine competition, the wine has been tasted by several different people, and they have all more-or-less agreed that the wine is of a certain quality. More than one person has liked it. Another difference is that wine scores give the illusion of being exact; a 94-point wine is supposedly better than a 93-point wine. Wine tasting and wine quality are never that exact. One can argue that it is a more realistic evaluation of the wine with ranges of scores that give a medal. For example, “a score above 92 is a Grand Gold”. (Competitions usually don’t publish the exact scores, just the medal.)

Some people prefer the scores of a certain individual taster, “I know I have the same preferences as the wine critic John Doe, so I go with his scores”. But in reality, very few wine consumers care so much about it that they get to understand how different tasters score.

So, for me, a medal (preferably from a well-run and reputable competition) does carry a weight and does give an indication of quality.

The work of the jury / the tasting panel

Most competitions work with tasting panels of between 5 and 7 people. They sit around a table and have the wines served by a wine waiter. The wines can be served in a “steady stream” one after the other or in a series of some kind.

Some competitions function by “self-service”; the bottles are “hidden” in bags, and the tasters serve themselves. According to Meninger, this is the case, for instance, with the International Wine Challenge, where the bottles are put on the table. This is definitely not ideal. Unfortunately, you can get a lot of information by holding the bottle and by seeing the top of the neck of it (e.g. weight of the bottle, a recognisable shape or bottleneck or something else). Even if one tries not to be influenced by it, it is very likely that it will influence the taster. It is much better if the taster never touches the bottle and ideally doesn’t even see it, not even in an anonymising bag.

A serious wine competition shouldn’t be self-service, in my opinion.

The two bottles below illustrate how revealing a bottle can be, one has the name of the producers on the neck of a very heavy bottle, the other is with screwcap.

In most cases, each taster gives an individual score, and the wine is then given the average of all the scores. Sometimes, the scoring is not quite individual. Instead, the panel discusses the wine before the tasters put a “pseudo-individual” score. Sometimes, the panel is supposed to agree on one common “panel score”. More on this later.

This brings me to a few of the fundamental differences between wine competitions.

Individual scoring or collective scoring? Discussion or no discussion in the panel?

Does each taster give an individual score independently, or is there discussion among the tasters around the table? These two approaches are likely to produce very different results.

Personally, I am much in favour of each taster tasting individually and scoring individually. If there is a discussion around the table before you decide on your notes, you will inevitably be influenced by what others say. We, tasters, are all experienced tasters (or should be) and have been selected to participate based on that. So we should be able to judge each wine by ourselves.

If someone says, “There’s some liquorice in this”, you will find it. Not too bad, perhaps. But if someone says, “Isn’t this a bit too volatile (or perhaps oxidised)?” then I can almost guarantee that some tasters will go in that direction and possibly downgrade it even if they actually liked the wine originally and didn’t find it volatile.

Tasting wine is such a subtle craft, and we, tasters, are very easily influenced by what other people say, even if we are very experienced tasters. Around a tasting table, there is likely to be someone who has more prestige, maybe the panel president/chair, with or without real merit, and what they say will most certainly influence others. Or someone is particularly vocal and opinionated. To me, the panel is composed of different people because these differences contribute value. Rubbing out different opinions by discussing risks decreasing the value of the panel.

Most of the competitions I have participated in work with independent scoring; each taster gives an independent score before any discussion around the table. I almost always find “discussion panels” less valuable. As a taster, everyone is far too impressionable by others. But this is usually flexible. Even if you basically score individually, if there are major disagreements on a wine, you can discuss them and potentially change your score. But that happens rarely and should only be an exception. You can also have discussions after giving your individual score to understand the reasoning the others had, especially in the case of wide differences. Your score is yours, but you can also listen to others’ arguments (after scoring).

I gather that the two major UK competitions, the DWWA and the IWC, work with discussion panels, but I have never participated in either of them, so it is only based on what I have been told or read. That risks giving too much weight to people with prestige, supposed experts, or simply people keen to voice their opinions. As Simon Woolfe, a Decanter DWWA judge, says, ”Many gold medal winners in DWWA would never have got over the line without discussion, retasting and encouragement from the panel chair.” (See more in the reference at the end of the text.) If that’s the case, what’s the point of having a diverse and experienced tasting panel if one person’s view is pushed onto the others? Doesn’t this defy the whole purpose of having a tasting panel? The point, it seems to me, is not to have one person’s preferred wines given gold medals but to have a collective view on the quality of the wine.

Otherwise, how does this “encouragement from the panel chair” work? (Or someone else than the chair who argues.) So, he/she pushes the panel to raise the score for certain wines. He/she knows better? Is the panel chair a better taster so he can tell the others that they are (most likely) wrong? Does he/she know more about how the wine should taste than the others? Isn’t that then a sign of that the other panel members are not quite as experienced as they should be?

A few of the competitions I have judged in have had the format where the panel is supposed to discuss and agree on a score (or adjust the individual scores after discussion). If there is a certain disagreement on the score, what this results in is usually that the one who is most different finally says, “okay, I’ll relent so we can finish the discussion and get on with the next wine.” But have they convinced me that my original assessment was wrong? Rarely.

I think you have to accept that others can have different opinions on a wine than what you have. But difference of opinion doesn’t mean that your opinion (or theirs) is wrong and needs to be adjusted. That’s just how wine tasting works. Appreciation of quality (and typicity) is subjective.

Or to put it in the words of Meininger International (who runs the Mundus Vini competition): “One rule that all serious competitions naturally share is the ban on discussion during the tasting of each sample.” (see reference at the end)

Tasting in categories or tasting blind?

This is another fundamental differentiation between competitions: Do you taste blind, or are you given information about what wine you are tasting, so you are tasting in pre-defined categories?

The CMB is an example of a competition where you taste blind. You have, in most cases, no information about what kind of wines you taste. The wines are served blind in series of between 8 and 20 wines that have some coherence, some commonality, but the tasters do not know anything about what is in their glasses. It could be a series of sauvignon blancs from around the world (or from Sancerre, or…), it could be bordeaux blends, it could be Beaujolais, it could be… You usually do get the vintage, which I’d rather not get, and I usually ignore it (what’s the point to have it?) and sometimes the information that it is a tank sample (yes, useful) or something similar.

This means that you have to taste and evaluate the wine purely based on what is in the glass. A genuine blind tasting that makes you focus on the “quality” of the wine.

Another way of organising a tasting is by organising the flights or the whole tasting in categories. For example, one panel tastes white burgundy. Another panel taste New World bordeaux blends, or Rioja, or… And they are often categorised into price bands. For example, the Decanter DWWA has these price bands:

- up to £14.99

- £15 to £24.99

- £25 to £49.99

- £50 to £99.99

- £100+

So, in essence, you know pretty much exactly what you are tasting. This fundamentally changes the tasting from being a neutral playing field about quality to instead being an exercise in “typicity” (in fairly narrow price bands). You’re no longer tasting to see if this is a good quality or outstanding wine. Instead, you are likely to think, “Does this taste like a £50+, but less than £100, Rioja SHOULD taste?”. This, to me, is not so much evaluating quality but instead evaluating if the wine conforms to an imagined mould (a mould that may not be relevant for a consumer).

Or as a Decanter DWCC taster (Simon Woolfe, see end note) has expressed it: “As judges, we know the country, region, sub-region, grape variety, style and price category of the wine”. This, in effect, removes much of the “blind” in a blind tasting.

Yet another drawback is that a £14 wine can never “win” over a £30 wine, whereas in the real world, it can certainly happen.

An extreme example of this is The Nordic Wine Challenge, where the categories are so narrow that in some categories, there are only a handful of wines.

Organising a competition in geographical or grape categories results in the tasing focussing on “does this wine taste as it should?” rather than on “is this wine good?”. I think “quality” is more important than “typicity”. Defining quality is not easy, but defining typicity (and judging wines on it) is even more hazy.

Scoring “quality” or scoring “typicity”?

Quality is subjective, not objective (and so is “typicity”)

I think this is one of the biggest differences between competitions. Do you taste for “typicity” or for “quality”.

The drawbacks of scoring for typicity, as described above, as most tasters probably do with wines only tasted half-blind, i.e. you know what kind of wines you’re tasting (the country, region, sub-region, grape variety, style and price of the wine), is also that this is even more difficult to define than quality. If you are tasting a series of sancerres of recent vintages and you get one that is a bit oxidised in style, what do you do? It is certainly not typical, but it might be an excellent wine all the same. And perhaps the winemaker consciously makes an oxidised style? Is that wrong? It is certainly not typical. Is a sancerre supposed to be more or less aromatic, more or less body than, e.g., a New Zealand sauvignon blanc? Each taster has, no doubt, a different idea of what is “typical” for a particular category of wines.

The fundamental question then is, of course, is a wine good just because it is “typical”? My answer is no. (The counter-argument that “the consumer expects the wine to taste in a certain way, so it should taste like that” is so far from reality that it’s hardly worth debating.)

Judging more or less totally blind on stand-alone quality makes more sense to me in a wine competition like this. You do not know what type or category of wine you taste. It has a lot of challenges, too, but it is quite different. Quality is fundamentally subjective. (Emile Peynaud said, “The most important criterion of quality, if not the only one, is that the wine is good”. What is good?)

There are some lines of thought that say that ”quality” can be evaluated in a neutral or objective way. That, in my opinion, is mistaken. Take, for example, the “BLIC” model put forward by some as an objective way to evaluate quality: Balance, Length, Intensity and Complexity. They are helpful parameters to evaluate a wine but not neutral or objective. Both balance and complexity are very subjective. What is, for example, the objectively best and balanced level of tannin or acidity or oak flavour in a certain wine…? It depends on your personal preference. There are, for example, great difference of opinion between different nationalities on this. Length and intensity are not necessarily good (a wine turned to vinegar has both in abundance). The “L” and “I” are good only if they are “nice” or good and nice is subjective.

And yet, in a tasting panel, we usually roughly agree. So there are certain fundamental qualities in wine that most (but not all) tasters can agree on. For most wines. As long as we stick to a limited collection of tasters. At the same time, one has to accept differences of opinion. This is perhaps one of the important points that make wine competitions useful, after all. Even if taste and “quality” in wine are fundamentally subjective, if a group of experienced tasters agree that a wine is good, then there’s some value in that opinion and a likelihood that more people will like the wine. (Although you might not agree.)

Maybe you’ve heard of the story of the annual wine competition in Chile. Usually, the jury was made up of mainly Chilean tasters. Usually, it was more or less the same wines, the same producers that got the best medals. One year (quite a few years ago) the organisers had the brilliant (?) idea to invite a lot of British tasters instead of the usual Chilean judges, since the UK was a big export market. A shock when the results were announced: it was not the same old producers that received the medals that year. The mainly British jury preferred different wines than the usual mainly Chilean jury. Were the Brits wrong and the Chileans right? Or the other way around? No. Rather, it is an illustration of that taste is also dependent on culture and tradition. British wine drinkers have different taste preferences, different tasting traditions, than Chileans. Not better or worse, just different. There’s no objectivity in taste. (But yes, there are some things most of us can agree on.)

One of my co-tasters in a recent CMB competition was the author of a PhD dissertation in oenology on the subject of typicity. In it, she points out the difficulty of pinpointing and agreeing on what sensory (tasting) typicity is and then identifying typicity in wines. She also points out that typicity is not the same thing as quality. (And finally, that quality is fundamentally subjective). (Coline Leriche: Etude de la typicité sensorielle d’Appellations d’Origine Protégée dans un contexte régional, 2020)

So, some competitions are all about some imagined “typicity”; others are more focused on the “quality” of the wine.

I prefer the competitions where you taste truly blind and thus judge the wines purely on quality.

“Competitions make money, so it’s bad or corrupt”

One reproach that is sometimes mentioned regarding wine competitions is that they are commercial enterprises organised to make money for the organisers. “They’re money-spinners.” “They charge a fee to the producers that send in their wines!” That seems to me a misguided critique. What else should they be? Organised by governments or charitable organisations?

There is nothing wrong with having a profit motive. Quite the contrary. It is the same for everyone, journalists write about wine in the (often vain) hope to make money, wineries make wine to make money, sommeliers serve wine in restaurants to make money. As long as the competition is well-organised and professionally run, criticising it for having a profit motive makes no sense.

Awarding medals

Sometimes people criticise competitions, especially grape variety focussed competitions, with arguments like “those gold medal-winning chardonnays are quite obviously not the world’s best chardonnays”. Correct, they are not. But that’s not the point. This criticism seems based on the (ludicrous) idea that all the world’s chardonnays would participate in a competition. How else can you choose the world’s best?

A wine competition doesn’t try to identify “the world’s best”. The objective is to give merit to good wines participating in the competition. And, by the way, there is no “world’s best chardonnay”. It depends on what style and flavours you like. In wine, there is no “world’s best”. There’s only “my best” and “your best”.

(The same basic errors and fallacy is found in initiatives such as “the world’s 50 best restaurants”, “the world’s best wine list” etc.)

Another critique that is sometimes directed at competitions are things like “the wineries are simply paying for getting a medal; it’s rather corrupt”. Perhaps there are some suspect competitions where it happens like that. But in the competitions that I have participated in, the tasting panel (the judges) have certainly done their job in a very serious and professional way and I have never had any reason to believe that the organisers go behind our backs and manipulate the results as the criticism implies. Such a competition would not only be corrupt but it would quickly lose its credibility and have difficulties attracting judges.

Many competitions award three levels of medals. For instance, the Concours Mondial (CMB) awards silver, gold, and grand gold, others have bronze, silver and gold or something similar. The Decanter DWWA has an astonishing five levels: bronze, silver, gold, platinum, and best in show, plus to added supplementary mentions: commended and value.

Most competitions that I know of award medals to a maxim of around 30% of the participating wines. This seems reasonable.

For example, I believe that the Concours Mondial gives Grand Gold to around 1% of the wines, Gold to 10-15% and Silver to 10-15%, with a maximum total of around 30% medals. 30% is also what the OIV recommends as a maximum (see further down on the OIV).

Everyone wins!

There are some exceptions to this 30% rule. Perhaps most remarkable is the Decanter World Wine Awards DWWA, which awards medals to around 80% (!) of the participating wines. According to Vitisphère, the 2023 edition had 18,250 wines tasted; 50 Best in Show, 125 Platinum, 705 Gold, 5,604 Silver, and 8,165 Bronze for a total of 14,649 medals. 80.2% of the participating wines had a medal. 5% had Gold or higher. If any, this seems to be a competition where you’re fairly certain to get a medal if you simply pay the participation fee.

I have seen a comment on this from a DWWA participating taster, saying in effect, (my wording:) “but they were almost all very good wines so they were worthy medals, 80% was fine”. But that invalidates the whole point of a competition, doesn’t it? The purpose is to eliminate the majority of the participants, no matter how good they are. Can you imagine in the Olympics saying, “In the finals of the 10,000 metres, all runners were under the magic limit of 27 minutes, so let’s give a medal to all of them”?

The other big British wine competition, the IWC, seems a bit more modest, with only 5,880 medals in the last edition (total number of samples unknown). According to Meininger International (see reference at the end), the IWC gives out some 35-45% medals. I have seen an (currently unverified) number of samples at 12,000 which would mean 49% medals. Also, an astonishingly high number, one chance in two to get a medal.

The scoring system used in the competition has sometimes been discussed. How do you, as a judge, come up with a score? In practice, it is not very important; a competition can use a 0-100 scale or a 0-20 scale or something else. It can use an arbitrary unstructured scale (“score in any way you want, as long as you come up with a number”), or it can be a structured scoring system. It does not really matter as long as the tasters calibrate in some way in the group to score similarly and coherently. What matters in the end is the total average score and if it gives the wine a medal or not.

CMB uses a structured scoring sheet similar to what is recommended by the OIV, giving points to various elements of nose, palate, finish and overall impression. But this structure is, in my experience, in practice largely irrelevant; the tool structure is mainly used as a backward counting tool for a judge to come up with a score that fits with the medal he/she thinks the wine is worth.

Reasonably, at the end of the competition, the scores are statistically normalised so that a reasonable number of medals are given. Most competitions, for example, OIV-sponsored competitions and the CMB, adjust the levels needed for a medal so that no more than 30% of wines get them. Some competitions award many more medals as we’ve seen above.

Bigger competitions let the tasters work with computers. Smaller competitions sometimes use paper notation.

Does the colour make a difference?

Thus, there are different levels of medals. Does it make any difference for consumers? Frankly, I think it makes very little difference for a wine on a shop shelf what colour the medal has. I doubt the shopper will look closely and think, “Only bronze, then I’ll pass”. I suspect that what counts is medal or no-medal.

“The best wines don’t participate in competitions”

Another criticism that is sometimes voiced is that the best wines don’t participate. This is mostly correct. But there’s nothing surprising in this, nor anything that diminishes the value of a competition. Wine competitions are essentially a marketing tool to help bring lesser-known wines out into the spotlight and a consumer guidance tool. Wine celebrities (famous wines) may think that they don’t need that.

For famous names there might also be a certain risk involved. What if they don’t get a medal? How embarrassing…! Well, no, not getting a medal would not be embarrassing since it is never (to my knowledge) made public which wines participate and don’t get a medal. But it might be embarrassing for a famous name to get a “lowly” silver and not a Grand Gold, of course.

The composition of a tasting panel

The composition of a tasting panel will make a big difference. I like panels that have a mix of different people, different nationalities, different backgrounds. That can make for a more balanced and nuanced view. In my latest Concours Mondial panel that I chaired (Monsieur le Président!), we were five people: one Australian, one Swede, one French, one Italian, and one Spanish. We had two journalists, one jurist, two oenologists, one wine buyer, one PhD, one MSc, one MBA, one wine region representative, and no doubt some things I forget (people had multiple hats).

Different people taste differently and have different preferences. To caricaturise, I could say that oenologists taste by looking for faults (“this is not as it should be, so I score it low”), wine buyers tend to look for “sellability” (“this is something that shoppers will like”), etc. However, experienced and intelligent tasters will make an effort to detach from their professional role.

There are also cultural and national differences. Some nationalities prefer certain types of wines, others prefer other types: some like more oak character, some abhor tannins or high acidity, some want a touch of residual sugar etc.

In the Concours Mondial CMB tastings, which I most frequently participate in, there are judges from probably more than 30 countries, with many different backgrounds: writers/journalists, buyers, “influencers”, oenologists, winemakers, sommeliers, chemists, retailers, etc. Little (if any) importance is given to a famous title; rather, the focus is on wine experience and tasting experience. Again a point where the British competitions seem to differ, more likely to put an emphasis on taster’s titles.

In most competitions (at least the ones I’ve done) there’s a level and fair “playing field” for judges. My opinion counts as much as my neighbour’s. All tasters’ opinion are valued equal. If you are invited as a taster/juror, you are considered competent and experienced enough to have an opinion. This is, in my experience, a correct choice almost always. Most of the tasters I have met in competitions have been there for good reasons, knowledgeable, professional. The only difficulty that sometimes comes up is tasters who judge on “how should this taste” (an impossible task in my opinion, especially when you don’t know what you’re tasting) rather than “is this good?”, or tasters who look mainly for faults (what is a fault? Not always easy. Volatility? Oxidation?… Depends on how much and on your preferences).

Here, too, the British tastings seem to function differently.

The International Wine Challenge IWC has a multi-tier hierarchy of judges: associate judge (=juniors), (plain vanilla) judge, senior judge, co-chair and panel chair. You work your way up through the hierarchy after a few years, unless you have a famous title, in which case you’re injected automatically higher up in the hierachy, just like a nobility with a peerage and seat in the House of Lords. Sir Peter, Sir Paul and Lady Mary on the tasting panel. My understanding is that the Decanter DWWA has a similar hierarchy. Perhaps a hierarchy with junior to senior judges etc is due to that they recruit junior and inexperienced people to sit on the tasting panels?

Are tasters remunerated?

None of the competitions that I have participated in has paid the tasters. From what I gather, here again, the British competitions are different. They do pay the tasters. Nice. In principle. But only a very small amount of money. I understand this is something like €100 per day or so. Unless you are a famous taster (and thus named a “panel chair” or some such thing) when you get paid more.

This creates the illusion that the UK tastings are more (financially) “fair” towards tasters; they pay the tasters. In fact, it’s the other way around.

The Concours Mondial and other competitions I’ve attended don’t pay the jurors, but they do cover travel, hotels, and (most) meals during the competitions. And give some additional benefits to the participants, like the opportunity to discover and explore a wine region (where the competition is held).

The British competitions are different:

The UK competitions pay the tasters but (as far as I know) don’t pay for any expenses. So if you want to participate you have to pay for your own travel to London, hotel in London and possibly extra meal expenses. That is not even remotely covered by the small payment that you receive. Unless you happen to live in London. So, in practice, for a non-Londoner, it seems that the taster actually needs to pay (expenses) to participate. Unless you are a famous wine person when they probably will pay your expenses or at least a much higher fee. I have not tasted at the UK competitions so this is based on hearsay. If this is not how it works, please feel free to clarify.

This must have a big impact on the selection of the tasting panel. Hardly many people will pay their own way to participate in the competitions so I expect the judging panel would be much more UK centric.

In most European and international competitions, there’s the added benefit to the tasters that there are mostly wine-related activities in the afternoon. Usually, they have panel tastings is in the morning and the afternoons are dedicated to winery visits or other wine and gastronomy related activities. This is not the case for the UK competitions as far as I know.

How many wines are tasted by the judges?

In a morning tasting session, a panel usually tastes between 35 and 60 wines. This means that each wine is given a handful of minutes of attention. Most competitions only taste in the mornings and have other wine activities for the judges in the afternoons.

Not so for the UK competitions, which also taste after lunch, is my understanding.

It is actually quite hard work to taste so many wines. It requires a lot of concentration and it also takes a toll on your palate (and teeth). It is quite beneficial for the quality of the tastings not to taste in the afternoons. I wonder if the afternoon tasting panels have quite as alert palates as the morning ones, in the competitions that do AM and PM.

Can you really evaluate a wine in so short a time?

One of the criticisms sometimes directed at competitions is that the tasters spend so little time on each wine, they don’t give the wines a fair chance and can’t make a fair evaluation of them.

I think you can. You don’t need that much time to get a mostly accurate impression of a wine. Wine competitions are not about making elaborate tasting comments. It is mainly a question of judging the overall quality of a wine, plus some short comments on style and flavours in some cases. You don’t need a lot of time for that.

In some competitions, the wines are tasted several times, especially the wines that are potentially given medals. That might be useful, but overall, I think it is superfluous unless there are some big doubts about a wine. Normally, a panel of 5-7 tasters should be able to fairly evaluate the wine in one go. It is, after all, not a life-changing make-or-break situation for the wine.

(I am “judging” in another type of “competition” too, where I would argue the opposite, that many opinions and repeated reviews are important. I am on the admissions committee of one of the world’s leading business schools. Each candidate submission is looked at by probably twenty people in total, each with a different perspective. But in this case, it is a question of potentially life-changing decisions.)

One should also keep in mind that other types of wine ratings, such as scoring and commentary by wine critics or journalists, are often done in a similar situation: in big tastings with only a handful of minutes spent on each wine. So, the situation is essentially the same for wine competitions and much of wine commentary that is published by individual critics.

Super juries

As mentioned above, some competitions taste the wines multiple times. Again, the UK competitions seems to stand out on this, tasting some wines multiple times and in the end the top scoring wines being retasted by some kind of “super jury”.

As Robert Joseph, long-time organiser of the International Wine Challenge says, “I also like the fact that wines at the IWC are tasted up to four times before they leave the process, and that all entries are sampled at least once by a ‘super jury’ – including reliable palates such as Tim Atkin MW, Charles Metcalfe and Oz Clarke – to ensure fairness and consistency.” (See more in the link at the end of the text. This is a quote from the text but it must have an error, surely it should say “all entries eligible for a top medal”? They super-jury can hardly taste all 10,000+ wines.) Perhaps that kind of super-jury can be beneficial sometimes (however, see my counter-argument above). But it does have an important drawback: the personal style and flavour preferences of Atkin, Metcalfe, Clarke, and a handful of other super-judges will dominate the top echelons. As mentioned elsewhere, both “typicity” (which is, to a large extent, what the IWC judges) and quality are subjective, not objective. In my view of wine.

Why participate as a taster/judge in a competition?

Why do people choose to participate in wine competitions? Why be a taster? After all, you’re spending several days, maybe a week of your time, and you’re not getting paid. Well, there are many reasons, and they probably vary from person to person. Here are some.

First of all, I find it quite interesting to taste a large number of wines blind. You can learn a lot from this kind of tastings. You can get a good grasp of, for example, a grape variety in a varietal competition (sauvignon blanc, grenache, vranac/vranec, marselan…) and, not least, understand the great variety of wines that any grape can give. (No, sauvignon blanc is not all grassy and exotic fruit.) Or of a wine country/wine region. It depends on what kind of wines you get to taste in your flights, but you learn a lot from them

Most competitions give the judges a list of the wines after the tasting so you can see what you have tasted, sometimes including your scores and any comments you wrote. Some competitions don’t give the judges the list of wines. This is a big mistake and seriously diminishes the value of the tasting for the judges. The competition should absolutely give the tasters information on which wines they have tasted.

You also learn a lot from others, your panel and other people that you discuss with during the competition. Sharing and exchanging views are important – mainly after you have decided your own score.

However, perhaps the most important lesson you learn is one of humility. Humility in front of the great wide wine world. If you taste the wines blind then you often try and guess – for fun – what the flight was about. Was this sancerre? Was it perhaps Austrian gruner veltliner? Was this champagne or perhaps franciacorta? You are almost always wrong.

No matter how experienced a taster you are, no matter what fancy letter combination you might put after your name, identifying a wine without knowing anything about it is very, very difficult. You guess wrong nine times out of ten. At least. No matter how experienced you are. We taste blind every day at home and try and identify what it is. We’re rarely correct.

Another exercise in humility is what is practiced by the Concours Mondial CMB: In each tasting session (with 30-60 wines), one wine is served twice. The taster never knows which or when. Do you give the same score/description to both (the same wine but at different occasions)? Giving identical scores both times is rare. A narrow band of a few points is more common and makes you satisfied. How you perceive a wine also depends on what has come before it. The apocryphal taster who can identify most wines correctly does not exist.

But “guessing wrong” is not a problem. Wine is not about “guessing right”. It is about a drink that should taste good and give pleasure. And sometimes — ideally — connect you with culture, geography, history, people…

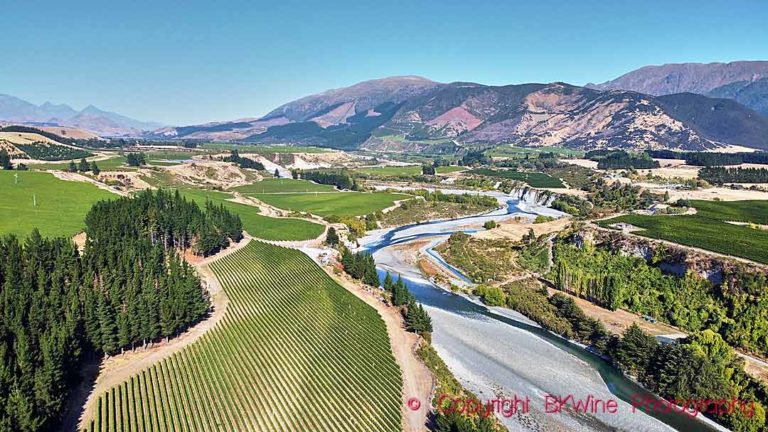

The Sauvignon Selection by CMB (Concours Mondial de Bruxelles) showcased the spectacularly beautiful Styria/Steiermark wine region in Austria when it was held in Graz.

Participating in a wine competition also gives you the opportunity to discover new wine regions, the region where the competition is organised, where you might not have been before. It also gives these regions a chance to market themselves to a group of professionals. I have discovered and learned a lot about many wine regions in this way: Alentejo, Croatia, North Macedonia, China, Steiermark (Austria), Sicily, Uruguay, Sardinia, Switzerland,… (This is, of course, less the case for the London- or Paris-based competitions.)

And finally, wine writing is, in fact, a pretty lonely business. You don’t meet people in the office because there is no office. So, the wine competitions are also an important networking opportunity for people working in wine, writers/journalists, buyers, “influencers”, oenologists, winemakers, sommeliers,… Meeting colleagues.

Do medals “work”?

Do wines that have received a medal sell better? Is it a good marketing tool? In general, studies indicate that, yes, medals are a good signal to consumers. See, for instance, “The Causal Impact Of Medals On Wine Producers’ Prices And The Gains From Participating In Contests”, mentioning a 13% impact on price.

But it depends. Some markets are less keen on medals.

One would hope that consumers could tell the difference between a good medal and a not so good medal. (How much is a medal worth from a competition that gives 80% of the wines medals?) But I doubt that is the case. I fear that most consumers have no idea of the reputation of different competitions. It is probably more important what nationality the medal is. French medals work better in France. For example, the Salon de l’Agriculture competition. British medals work in the UK but less so in France. Australia, also a country keen on wine competitions, prefer Australian medals. If people even bother to read what it says on the medal…

Equally, I don’t think the colour of the medal makes that much of a difference. For the consumer. A medal, any colour, is good. It is probably more important for the producer (or the wine buyer, distributor). A Grand Gold is a bigger confidence boost than Silver.

OIV

I also need to mention the International Organisation of Vines and Wines, an international standard-setting organisation for wine-producing countries. They have developed a framework for wine competitions where they set out standards and methodologies to run, in their opinion, effective and fair wine competitions. Competitions who follow their guidelines can get an OIV Patronage. For example, limiting the number of medals to a maximum of 30%, not influencing judges’ decisions by panel discussions, tasting sessions preferably only in the mornings, etc. (Some other of the OIV rules are harder to understand though.)

None of the big international competitions follow these guidelines in detail, as far as I know. The Concours Mondial de Bruxelles CMB is fairly close but has its own methodology.

Europe, yes — What about USA, Australia…?

This discussion is, admittedly, very Euro-centric. The competitions I know well are mainly European or organised in a European style.

I understand that Australian competitions can be quite different, for example with long rows of 20-30 wines that you can taste back and forth as you wish and change your mind on as you go along the flight and also discuss with other tasters. At least some of the competitions. For some you need to do a pre-competition training (that you might have to pay for). Overall very different.

I know nothing about American (US) competitions. I have never participated in a competition in the USA (although I have attended a few in South America).

The day I am invited to participate in a competition in the US, Australia, new Zealand or any other non-European country, I will be able to say more about them. Invitations are welcome!

Conclusion

So, what to make of all this?

Any kind of wine rating, be it a competition or an individual critic’s comments is subjective and has its limits. It should never be taken as an objective truth.

Wine competitions should not be seen as something that can replace (or is better than) the work of a wine writer who visits a winery, walks in the vineyard, inspects all the tanks and tools in the cellar and discusses with the winemaker, tastes at length and in depth the wines of a producer. This is just as valuable, if not more. It is a different thing. Both extensive wine writing and wine competitions give valuable information to the wine consumer.

The competitions I have seen from the inside, that I have participated in, have been professionally run with competent and experienced tasters/judges. I think their results, the medals, are fairly awarded and point to wines of quality. I have certainly never seen any “pay for a medal” happening. Sometimes, the outcome is surprising, for example, humble wines being awarded finer medals than the famous names. But that’s what blind tastings are for. And, again, taste is never objective.

I prefer — and find more trustworthy and reliable — competitions:

- That award a reasonable amount of medals (not everyone can be a winner)

- Where the judges taste independently and give individual independent scores to get a diverse view on the wine (without discussions to influence you to move you to an average acceptable score)

- Where you judge on quality and not typicity, in other words, where you taste fully blind not knowing what the wine is, instead of half blind (knowing e.g. the country, region, sub-region, grape variety, style and price category of the wine)

But any well-run competition, even those that do not follow these points, no doubt gives useful information to the potential wine consumer.

So, yes, for a consumer, wine competitions do give an indication of (some kind of) quality, I believe.

Ideally, consumers should give a thought to how the medal-awarding competition works. Not all competitions are equal. Probably, this is wishful thinking.

If you want to delve even deeper into wine competitions, here are some alternative views, referred to in the text above:

- Are Wine Competitions a Load of Rubbish? By Simon Woolf. It has a lot of interesting comments and concerns, as well as some misunderstandings, some of which I address above, all from a fan of and taster in the Decanter DWWA. Unfortunately, it also to some extent contains arguments based on conjecture and innuendo.

- What’s the point of wine competitions?, by Robert Joseph. A well-argued piece on the benefits of “the British model” of wine competitions.

- The Confusing World of Wine Competitions. A reflection on the Mundus Vini competition and on other competitions by Meininger (organiser of Mundus Vini).

2 Responses

Sorry Per, rant incoming…

I judged for 10+ years and gave up when I realized how little they do for the industry. In my opinion they keep the industry hobbled and reliant on scores, rather than evolve beyond them. Importers demand scores, but consumers seem to find wines worth drinking with or without the scores.

One line in your story made me personally cringe most: “(RE:blind tasting)This means that you have to taste and evaluate the wine purely based on what is in the glass. A genuine blind tasting that makes you focus on the “quality” of the wine.”

Well that makes no sense. If my Albarino from Spain tastes like an austere Sauv Blanc from France, the quality of that Albarino is crap. The last time I judged at a competition, the whole table I was at thought a flight was Southern Spanish Mouvedre, and it was pretty darn good, too! Only problem is that when we found out what it was, it turned out to be Bordeaux(Medoc I believe). I would say a very poor example of what I want to drink when I grab a bottle of Bordeaux. I don’t want my Bordeaux to taste like southern Spain(15%+).

Double blind like at the CMB is ridiculous. They’d reject Jura due to volatility. Or Musar due to brett I”m sure. :)

I think the industry really needs to drop these profit-making machines and focus on giving consumers the confidence to not worry about getting the right wine and just enjoy the journey. And a note for the wineries: stop playing the lottery at a wine competition and start talking to your customers and selling wine with your own voice, not others.

Sorry, Per. I’m not picking on you; this is just a subject that really drives me nuts. We should be spending all the money on making the industry more sustainable and consumer-friendly, not more exclusive by saying there is a “right wine.”

Hi Ryan,

Nothing to be sorry about. I appreciate you taking the time to comment. We do have quite diverging opinions on this. I certainly don’t take it personally. I find it an interesting subject too.

I don’t think I ever argued that scores is the most important tool for wine consumers to select wine. If you read what we write, you will have noticed that we almost never use points. But if a consumer is standing looking at a shelf in a wine shop or supermarket, he’s not going to go online and start searching for articles about the 300 producers on offer. Medals can be a useful tool but they’re certainly not the be-all and end-all. They can also entice people to try something that they might not otherwise have thought of.

I do find evaluating the wine purely based on what’s in the glass both relevant, useful and revealing (not least that they can reveal that famous names don’t always deserve their fame). Much more useful than evaluating wines on if they happen to be typical, as you suggest. Typical is a super-hazy concept (and also something that, if applied as a criterion, risks reducing wine towards stereo-typicity).

It’s a curious example you chose with albariño and sauvignon blanc. They have a lot in common, in my opinion, so could easily be confused. As for the bordeaux example, I find it strange to say “they were really nice wines, but they were not as I expected so I’ll give them poor notes” (which seems to be what you say you would have done, if I draw the conclusion). It also raises the question of “what is typical?” What is “typical bordeaux” for example. Much of bordeaux is today with very ripe fruit, quite high alcohol, 14.5% is common, smooth tannins. Those 12-13% bordeaux are from the 70s. Many bordeaux drinkers love them that way (and certainly many of the top wines are like that). The difficulty of pinpointing what is “typical” is well illustrated by the (true) blind tastings at e.g. the CMB (or your Bdx flight). Over three days you have around 10-15 different flights. After each, one tends to guess “what was this we just tasted?” More often than not, you’re wrong. If typicity was easy and clear, one would mostly be right.

Jura — another example. They make a lot of chardonnay but in wildly different styles, from steely fresh exotic fruit versions to very oxidised sherry-like ones. What’s typical? The muscadet producer who wants to make something ambitious and delicious with limited yields, some skin-time in the press, maybe hints of oxidation and perhaps even a touch of oak should be penalised because he doesn’t make a bland, neutral, typical muscadet? He will be if one judges on typicity.

In fact, I think it’s in many cases the opposite that happens: if you taste on “typicity” you exclude (or give poor notes to) a lot of very good wines that don’t confirm to the mould. Put a Coulée de Serrant in a flight of Loire chenins, a Didier Dagueneau in a flight of Loire sauvignon blancs, an Anselme Selosses in a flight of champagne and they will fall out of the frame and scored down if you judge on typicity because they are all very atypical. Put them blind in front of an experienced taster and they will more likely appreciate the “quality” in them. It is the “typicity tastings” that eliminate the unusual and often exciting wines.

Another weakness with “typicity” is that it only works for the most famous regions/style. Who (taster or consumer) will know what is “typical” for AOC Chateaumeillant or AOC Gaillac or torbato from Sardinia or albana from Romagna or timorasso from Piedmont or North Macedonian vranec?

And this thing with “profit making machines” or “money spinners”… You sell wine and you organise wine tours to make a profit, don’t you? So what’s wrong with making a profit?

If I remember right, you do sell wine, so if someone comes and looks for a wine, will you refuse to give them advice? Voicing an opinion in a competition is not fundamentally different from when you recommend something in your shop. You say it has quality, a competition judge puts scores on what he thinks has quality. No one claims that competition medals pinpoint “the best wines” or the wines everyone “should” chose. They are positive signals that can entice the consumer to try a wine, just like when you say “this is a nice wine” in your shop. I’d guess that more than 95% of all wine is bought in a neutral situation where the buyer don’t have a shop keeper to advise him. Can it not be better to by enticed by some medals on unknown wines rather than being guided by the big-budget marketing campaigns from the big brands that the shopper otherwise would be influenced by?

/Per