Pinot noir is not just Burgundy and Champagne. The grape is the ninth most cultivated variety in the world. It is planted on 115,000 hectares, of which roughly 30,000 hectares are in France. In other words, a lot is left for the rest of the world. In the relatively cool climate of New Zealand, it feels right at home. All wine regions in New Zealand have pinot noir vineyards; in some, it is a signature grape. Come with us on a journey through New Zealand’s wine regions and learn how great pinot can be here.

Of New Zealand’s 40,000 hectares of vineyards, 5,700 are pinot noir. That is the 4th most significant plantings of the grape in the world (USA and Germany are in 2nd and 3rd place). It is New Zealand’s most planted red variety. It is most famous in Central Otago on the South Island, but other regions, e.g. Wairarapa on the North Island, make exceptional pinot noir wines. The climate varies somewhat between the North and South Island, sometimes noticeable in the wines.

This is a longer version of an article published on Forbes.com.

A pinot noir refresher

Pinot noir wines are usually light-coloured, but can become more dense in warmer climates. Don’t judge them by their colour though. They have complex and intense aromas, but not much power, especially in cool regions like Burgundy. Red Burgundies are more elegant than powerful.

Pinots usually have high acidity and low tannins. The aromas are strawberries, raspberries, cherries, violets. They can occasionally have very ripe strawberries. Sometimes they have spicy or coffee notes from oak ageing, which, however, is less common than with cabernet sauvignon. With age, the wine can acquire a seductive character of forest floor and autumn leaves and a velvety finish.

Pinots are known for their light style, but that doesn’t mean they are weak. They have aromatic intensity and power, but a modest body and tannins. Pinot noir from New Zealand tends to be more concentrated with more ripe fruit than most Burgundies.

Read our full pinot noir grape profile here.

Let us look then closer at the New Zealand Pinot noir around the country’s regions, from south to north.

The South Island

Central Otago

In 1862, gold was found in Central Otago, and within a few years, the region became the richest in the country. Some gold diggers also planted vineyards, but they eventually fell into oblivion. The gold is also a thing of the past. When Marlborough first became prominent in the 1970s, few in the New Zealand wine industry believed that wine could be made in Central Otago. It was simply too cold. Central Otago is the world’s southernmost wine region, so the climate is challenging. But the long and dry autumn makes up for a chilly winter and a cool spring. Summer can get really hot, and the sun is intense. The Southern Alps act as a rain barrier. The vineyards receive less than 600 mm of rain annually, often much less. On the other side of the mountains, on the west coast, however, they get an incredible amount of rain, 2,000-3,000 mm a year, with certain years reaching 6,000 mm.

Another critical aspect of the climate, says Domenic Mondillo at Mondillo Vineyards in Bendigo, is the difference between day and night temperatures. “We can have 2 degrees C at night and 26 degrees C during the day. We harvest pinot noir earlier than our riesling.”

The sun in Central Otago is incredibly strong, with high levels of UV light (this is the case all over New Zealand), and many producers stress the importance of canopy management. Sometimes, you want to protect the grapes from too much sunlight.

Pioneers such as Alan Brady at Gibbston Valley Winery and Rolfe and Lois Mills at Rippon launched their first pinot noirs in 1987. After that, fame came quickly. Pinot noir from Central Otago is now counted among the world’s elite. The style is rich with dense fruit – but often with the pinot elegance intact – and intense aromas of red berries and dark cherries. The colour is unusually strong for pinot noir.

Pinot noir dominates Central Otago with almost 80% of plantings, which means around 1600 hectares. The climate varies between the sub-regions. The warmest and driest are Bannockburn, Cromwell, and Bendigo (these parts account for roughly 70 % of all the wines), and the coolest is Gibbston. Alexandra is the southernmost, with an even drier climate and extreme temperatures both in summer and winter. Wanaka, on the beautiful Lake Wanaka, has only a few wineries, including Rippon.

Do not pay too much attention to the subregions, though. There are differences within each of them and similarities between all of them, as well as vintage variations and, as always, differences between winemakers.

One of the pioneers in Central Otago is Felton Road in Bannockburn. Blair Walter, the winemaker, keeps the yield low for his pinot noir at 5.5 tonnes per hectare, which translates to 35-40 hectolitres per hectare. New Zealand generally has high yields, especially for sauvignon blanc. But it is important to keep it low for Pinot noir, says Blair. Perhaps that is one reason for his wines’ aromatic concentration, complexity, and lovely, silky tannins.

Also in Bannockburn, Carrick Winery makes concentrated och spicy pinot noir wines. The Excelsior Pinot noir has 18 months in oak barrels but is still a balanced fruit with a body that can handle the oak. Carrick has a range of natural wines, and a favourite is Pot de Fleur Pinot Noir with 100% whole-bunch fermentation. Refreshing and easy drinking.

Carrick’s Magnetic Pinot noir, a single vineyard wine from a small plot of 0.35 hectares, is planted with a particular clone called Abel, which, according to legend, was brought in illegally from one of Burgundy’s best vineyards in the late 1970s (it did, however, go through proper quarantine in the end). Now, it is used for some of the best pinots in the country.

New Zealand producers often emphasise the importance of choosing high-quality clones of pinot noir. Many prefer to plant several different ones as each has slight variations as to, for instance, resistance to certain diseases. The Dijon clones (named after the town of Dijon in Burgundy) arrived in New Zealand at the beginning of the 1990s and are much used and appreciated.

Pinot noir to try from Central Otago: Felton Road (Bannockburn), Carrick (Bannockburn), Mondillo (Bendigo), Rippon Vineyard (Wanaka), Peregrine Wines (Gibbston), Gibbston (Gibbston), Misha’s Winery (Cromwell), Quarts Reef (Cromwell), Mount Edward (Gibbston), Prophet’s Rock (Bendigo)

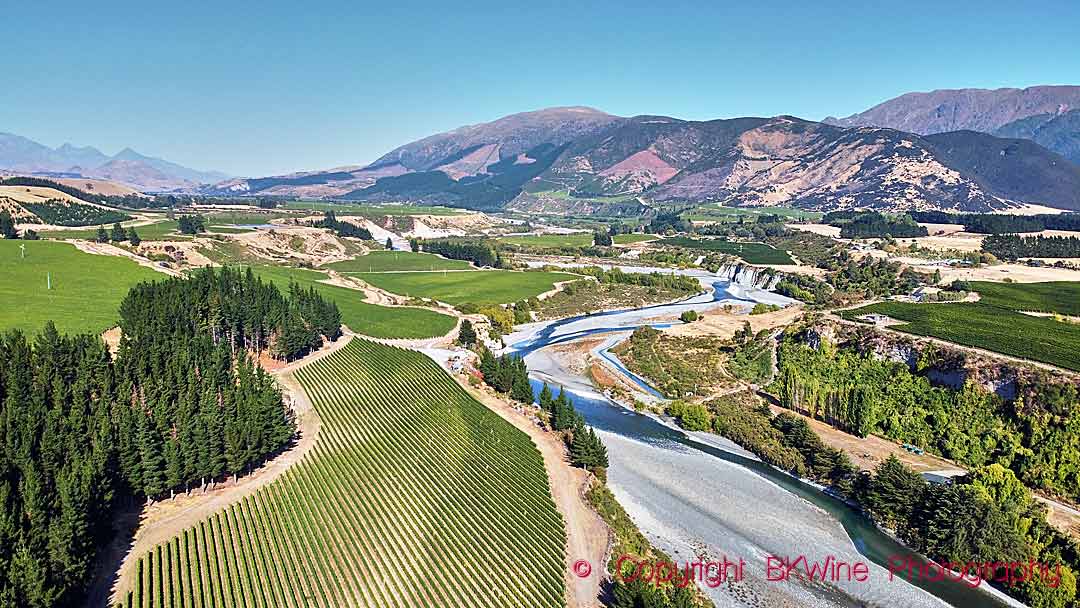

Marlborough

Sauvignon Blanc is the star of Marlborough and the grape variety that brought fame to New Zealand as a wine country. Marlborough has over 29,000 hectares of vines, 23,700 ha of which are Sauvignon blanc. Pinot noir, however, is doing its best to break the monopoly. It is the second most planted variety, with around 2,700 ha, half of all pinots in the country. Marlborough is on the northeastern part of the South Island. In good weather, you can see across the strait. Even though it is cooler than on the North Island, there is lots of sun. Marlborough has almost 2500 annual sun hours (Bordeaux has 2000).

The terroir is varied: glacial soil, gravel, greywacke (rounded, hard river stones), sediment clay, heavy clay, windblown loess. The rain pattern is different depending on where you have your vineyard, and Marlborough sometimes has very strong winds that challenge all the varieties, as well as pinot noir. There is no problem getting ripe grapes, but the quantity can vary.

Marlborough Pinot noir tends to be lighter and fruitier than the pinots of Wairarapa (see below) and Central Otago, with lots of drinkability. We have finesse, says Damien Yvon, winemaker at Clos Henri. “New Zealand is very excited about Pinot noir; it has a big potential here, and the regions are different in style. Pinot noir is getting important in Marlborough.”

Damian also points out the importance of managing the extraction. For the Bel Echo Pinot noir, “we work to restrain ourselves with extraction”, and he keeps the temperature at 25 degrees C, which is low for red wine, and he uses pumping over instead of pigeage. He uses only 8 % new oak for certain vintages for the ageing; the rest are old barrels. The result is smooth, floral, deliciously drinkable. The flagship Waimaunga Pinot noir has a rich, savoury character with leather, forest, and spices aromas. “Here, the clay soil gives a voluptuous style to the grape,” says Damien.

Auntsfield Estate was established by Graeme Cowley from Wellington in 1998, exactly where Marlborough’s first vineyard and winery was founded in 1873. However, Graeme and his wife Linda did not find out until later. Auntsfield is now run by their sons, Ben, the viticulturist and Luc, the winemaker. Together, they make some superb single vineyard pinot noir with a smooth mouthfeel and concentrated fruit aromas. “My parent’s passion was for Burgundy,” says Ben.

Tupari and Clos Marguerite are both in the Awatere subregion, a little bit to the south. It is only 20 kilometres southeast of Blenheim, the Marlborough capital, but it has fewer wineries and cellar doors, so it feels more secluded. It is cooler than most parts of Marlborough, and the harvest is later. The Tupari vineyards, however, benefit from warm days and soft slopes facing north (the warm side in the southern hemisphere). The result is an elegant, expressive pinot noir.

Marguerite Dubois at Clos Marguerite gets a lot of intensity in her wines, partly from very low yields. There is a silky mouthfeel and a typical nose of pinot of leather and forest floor.

Pinot noir to try from Marlborough: Clos Henri, Auntsfield Estate, Clos Marguerite, Nautilus Estate, Tupari, Fromm, Rockferry (a winery in Marlborough, but their flagship pinot noir is from Central Otago).

North Canterbury/Waipara Valley

Driving along the beautiful coast south of Marlborough (maybe stopping in Kaikoura for a delicious meal of green mussels and crayfish), you will eventually end up in Christchurch. Forty-five minutes before you reach the city is the wine region of Waipara (not to be confused with Wairarapa), which belongs to the more extensive area of North Canterbury. This is a cool area with cold winters. Waipara, however, is protected from the cold easterly winds. The grapes enjoy a long growing season.

Pinot noir is gaining recognition here, and often, you will find spicy and earthy aromas and a good structure in the wines. Sauvignon blanc is grape variety number one, and riesling, in third place, is showing very promising wines.

Pinot noir to try from Waipara Valley: Pegasus, Black Estate, Greystone Wines

Nelson

Nelson is at the northern tip of the South Island, north-west of Marlborough. It has grown from virtually nothing, just 35 ha, in the early 1980s to 1,200 hectares today. Not surprisingly, considering its closeness to Marlborough, Sauvignon Blanc is the most planted variety with half of the acreage, followed by pinot noir with 213 ha. Nelson is a bit rainier than Marlborough. They get an average of 960 mm compared to Marlborough’s 700 mm just an hour and a half east. To compensate, Nelson gets lots of sunshine as well.

“We have long sunshine hours but not intensively hot days, and this gives [our pinot noir] a framework of savoury, mushroom, umami notes underpinned by red and dark fruits with fine tannins,” says Rosie Finn at Neudorf, a top-quality Nelson estate. Rosie is the daughter of founders Judy and Tim Finn, who planted their first vines in Nelson in the 1970s.

Pinot noir to try from Nelson: Neudorf

The North Island

Wairarapa, Martinborough

Wairarapa is at the southernmost end of the North Island, near Cook Strait. It is named after Lake Wairarapa to the east of the vineyards. Pinot noir is planted on just over half of the region’s 1,000 hectares. Wairarapa is the southernmost, coolest, and driest of the North Island’s wine regions. It is often windy. Pinot noir likes it here, though, and the region has a reputation for making some of the finest Pinot noir wines in the country. The most famous subregion is Martinborough; others are Gladstone and Masterton.

The entire region has gravelly soil from old river beds that warm up quickly in spring. Frost can be a problem in the spring, though, and here and there in the vineyards, you see tall wind machines with propeller blades at the top. They are frost protectors; they set the air in motion and draw down the warmer air.

Martinborough has around 700 hectares of vineyards and just over 40 producers, most of them with small volumes. Many are only a short distance from each other, around the small town of Martinborough. Wairarapa got its first vines in the late 1970s. One of the pioneers was the now very well-known Ata Rangi estate. Another famous property is the Escarpment, which is a little further out of town in one of the driest parts of Martinborough.

Escarpment makes magnificent wines from Pinot noir. Full-bodied, densely structured wines with pronounced tannins. “We tend to get a lot of tannin, so we need ripe dense fruit to balance it,” says Tim Bourne, head winemaker at Escarpment.

But the wines are still elegant. This is important for Escarpments owner and legendary Pinot noir maker Larry McKenna. “A Pinot noir must be elegant, something you serve with game or duck; a serious red wine, but with finesse. It is not a Shiraz,” he told us when we visited Escarpment a few years ago during harvest time (Larry has since retired).

”To get the elegans, we don’t want the grapes to ripen too fast, so we have about 60% leaf removal around the fruiting zone with our Pinot. We want some exposure [to the sun] but not full exposure.”

They use whole bunches at various levels during fermentation. Their remarkable Kupe Pinot noir is generally up to 70% whole clusters. “When the phenolics are ripe, it brings a layer of complexity and freshness to the wine,” says Tim.

Their wines age well. We tasted Pahi by Escarpment 2011, a single vineyard pinot noir from 25-year-old vines. It is powerful and smooth, with layers of dark fruit aromas and a refreshing and dry finish.

Another Pinot noir favourite in Wairarapa is Gladstone Winery. Gladstone was founded by an Australian in 1986 and was later owned by talented winemaker Christine Kernohan from Glasgow. She sold Gladstone in early 2020 to Eddie McDougall, a winemaker and TV personality from Australia/Hong Kong.

The winemaker is Monty Petrie, who describes himself as a “hands-off winemaker.” The pinot noir and all the other reds are handpicked and fermented in small tanks; that way, the many small batches can get different treatments. His pinots are delicious, with abundant red fruit and some leather; they are balanced, not so extracted, and have a very pleasant mouthfeel. Dakins Road Pinot Noir comes from stony soil. For this wine, “we cherry-pick our best plots.” It has a little bit more new oak; it is rich and more velvety with dark cherry and raspberry aromas, and the structure is dense with nicely balanced tannins.

Pinot noir to try from Wairarapa: Ata Rangi, Escarpment, Gladstone Winery, Tirohana, Craggy Range

Hawke’s Bay

Hawke’s Bay is the largest wine region on the North Island. Vines have been grown here for a long time, at least by New Zealand standards. The first grapes were planted in the late 1850s by missionaries, and Mission Estate Winery is the oldest producer in the country still in existence. The climate is warm, even slightly warmer than Bordeaux. Bordeaux varieties, such as merlot and cabernet sauvignon, ripen well here, as well as syrah. Most vineyards are on former riverbeds with gravel, sand, and clay.

Hawke’s Bay is New Zealand’s oldest red wine region, but pinot noir is not a grape associated with the region. Pinot noir is in fifth place with 230 hectares. But the grape has grown in importance in recent years. It produces wines with delicate, aromatic fruit aromas and soft tannins and a relatively light body,

Pinot noir to try from Hawke’s Bay: Te Mata Estate