Making wine is pretty straightforward. Or rather, it was, once upon a time. Today it is more complicated. The fermentation, not least, requires the winegrowers to think carefully. They know that yeast turns the sugar in the grapes into alcohol, that stays in the wine, and to carbon dioxide that dissipates. They also know that yeast is found on the grape’s skin and in varying quantities around the vineyard and the wine cellar. But the big question is: can they trust this yeast? Or, should they instead choose a safer route and buy cultured yeast of the most common species, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, propagated in a laboratory? And thus gain more control over what happens during the fermentation and a more secure end-result?

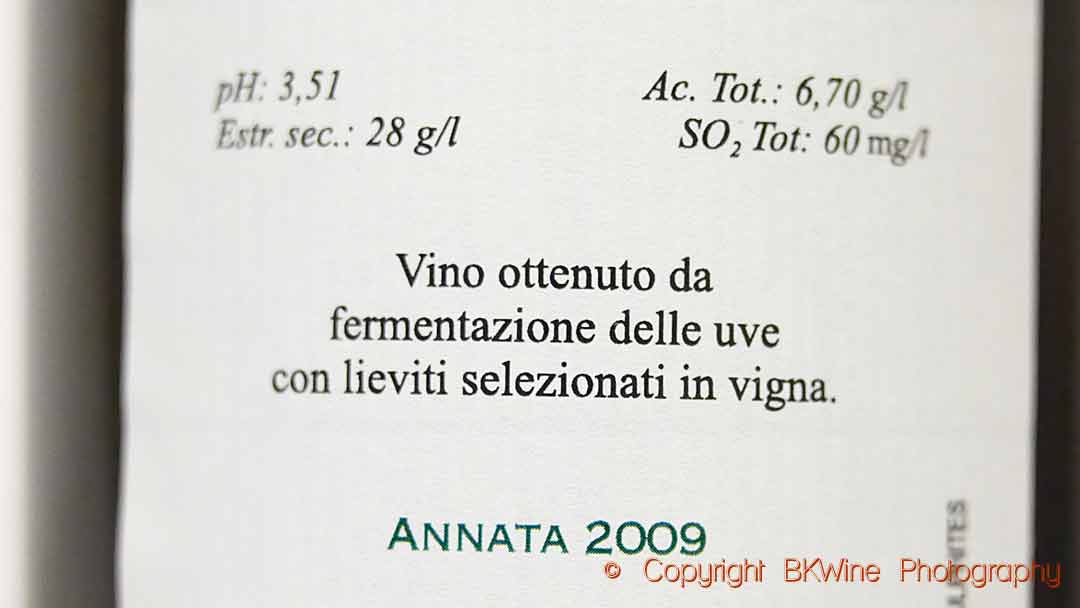

What you choose depends on several different things. Many producers think that the cultivated or cultured yeast is more reliable. (Cultivated yeast is often also called commercial yeast or industrial yeast or selected yeast.) They know that the fermentation will start quickly and continue until all the sugar is converted into alcohol.

A shorter version of this article has been published on Forbes.com.

Using wild yeast could be risky. (Wild yeast is sometimes also called natural yeast or indigenous yeast.) But those who do spontaneous fermentation, another expression for using wild yeast, think it works fine. And they believe that it is more natural to use yeast found in the wine’s immediate environment. And perhaps more importantly, they think it gives more character and complexity to the wine. However, there is not really any agreement in the wine world if that is really the case.

What is best

So, is one better than the other? Spontaneous fermentation or cultured yeast? No, not really.

Natural yeast is not one yeast, instead it consists of many different types of yeast species. Some of them are better than others at turning sugar into alcohol. Some can, if you are unlucky or careless, give bad aromas to the wine. Maybe you have heard of the wine fault called “brett”? It is an unpleasant smell (at least if it is too much) that is caused by a yeast called Brettanomyses.

In a normal winery environment, about half of the natural yeast is of the type Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the yeast used for wine, beer and baking. Other wild yeasts in the must can be, e.g., Kloeckera apiculata and Torulaspora delbrueckii. They are present mainly at the beginning of fermentation and have some significance for glycerol production and various esters. Up to about 30 different yeasts can be active during a spontaneous fermentation. Different types of yeast dominate during different phases of the fermentation in quick succession. When the alcohol contents rises, or the tank warms up, some die, and other, more robust varieties replace them.

One of the issues with using natural yeast, or doing a spontaneous fermentation, is that you cannot be sure exactly what kind of yeast strains that you will get in the must. So there is an increased risk that the fermentation will not proceed the way you want it. There may be unwanted strains that take over or it may not quite manage to ferment out the sugar, resulting in a “stuck” fermentation and a wine with residual sugar.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae is only found in low concentrations at the beginning of a spontaneous fermentation but will later compete with the other ones. It is always Saccharomyces cerevisiae that completes the fermentation at the end.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae is very well suited as the wine’s main yeast variety as it can work well in different temperatures, survive high alcohol content, high sulphur levels and low pH. All things that regularly occur in must being transformed into wine. It has the precious ability to ferment all the sugar. When you add cultured yeast to the yeast tank, you kill the wild yeast, but not always completely. Or to be more specific, the cultured yeast is so vigorous so that it completely takes over the fermentation from other weaker yeasts. It may be that the added yeast works together with the natural Saccharomyces.

Cultured yeast

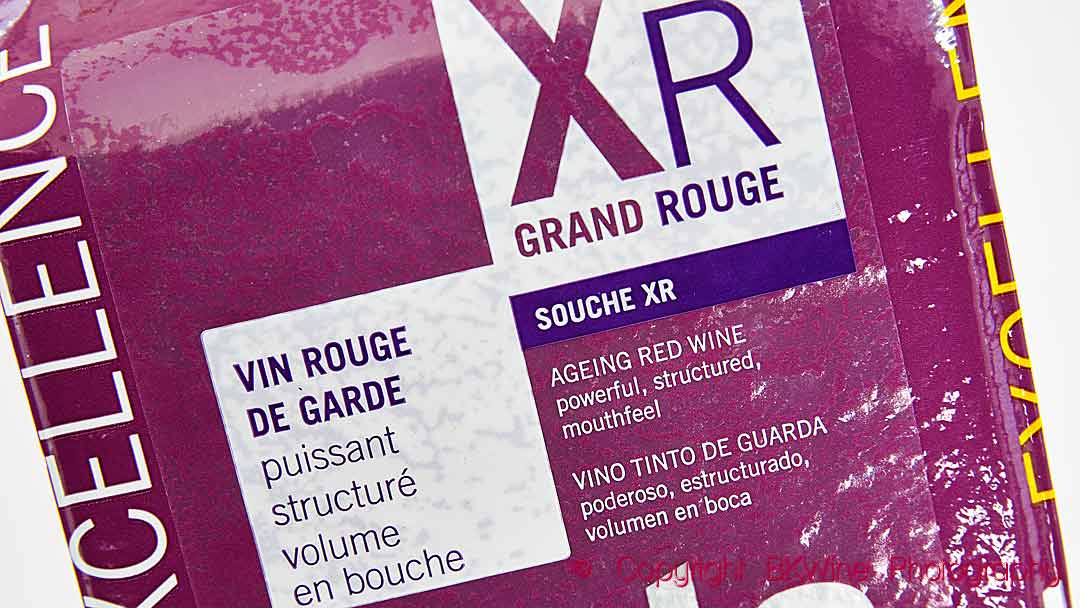

If the winemaker decides to buy cultured (“industrial”, “commercial”) yeast instead of relying on the natural one, it is not necessarily an easy choice which to work with. There are, in fact, several hundred different yeast strains on the market. Biotech companies, such as the Canadian Lallemand and the Danish Chr. Hansen constantly renew they ranges of yeast and innovate with new products.

In fact, the cultured or selected yeast originally comes from nature. They are yeasts that have been found in nature, have been tested and evaluated and deemed to have good qualities. They have then been purified and bred in a laboratory environment. They have been “selected” from what occurs in nature. So there is not anything “unnatural” about industrial or cultured yeast. Artificial or “manufactured” yeast does not exist. Neither are there “flavouring” yeasts, strains that can add a flavour that does not originate from the grape (more on this below).

So, each cultivated yeast originally comes from a vineyard somewhere in the world. This allows the winemaker, if he wants, to choose a yeast strain that comes from a region with similar conditions as his own.

Sometimes the yeast comes from a very well-specified vineyard. An example is Lalvin Clos from Lallemand, which originates from a specific plot in Priorat, in Spanish Catalonia. This yeast consists of selected Saccharomyces cerevisiae found on the carignan and grenache grapes that grow there. For three years, Lallemand’s researchers studied the wild yeast in this vineyard and selected the ones with the desired qualities.

Why choose one or another yeast?

With the yeast, the winemaker can, if he so desires, to some extent control the style of the wine. For example, some yeast strains are more efficient in processing certain flavour precursors that exist in the grape must and that will form thiols. This is a group of chemical compounds that in the wine give it aromas of passionfruit, citrus and other typical sauvignon blanc attributes.

So by choosing one or another yeast strain the winemaker can enhance or diminish these characters. But he cannot add them without the precursors in the grape. (The same applies, of course, if you use wild yeast. In some cases, one or another character can be highlighted or suppressed depending on the wild yeast, with the difference that in this case you do not necessarily know what will happen.)

Certain strains preserve colour and tannins or provide softness to the wine. Some are adapted to a specific grape variety, soil or climate or a specific kind of wine.

You can choose a yeast that works well in a must with low nitrogen levels (a problematic environment for the yeast that can make for a difficult fermentation), organic yeast, yeast for primeur wine, for sweet wines, for fruity reds, for strong, alcoholic reds. There is even yeast that can handle 18 % alcohol. Different cultured yeast have been developed (selected) to deal with all these situations that make life hard for a yeast.

The yeast Vitilevure Quartz from Champagne is effective when it comes to restarting a stuck fermentation (which can be very problematic). Another yeast from Champagne can withstand temperatures down to 4 degrees C and up to over 30 degrees C. It can restart a stuck fermentation with 15% alcohol content and 6 grams of residual sugar. Yet another character that is needed when making sparkling wine is a yeast that can work under high pressure (and restart when the alcohol contents is high) for the second fermentation in bottle.

Until about 10-12 years ago, all cultivated yeast was Saccharomyces cerevisiae. But a couple of years ago, researchers started experimenting with non-Saccharomyces yeast to see if they could combine some of the presumed positive qualities of the wild yeast (complexity, mouthfeel, body…) with the speed and control that fermentation with cultured yeast provides.

In 2009, Chr. Hansen’s introduced Prelude.nsac which was the first yeast on the market without Saccharomyces. Prelude.nsac contains 100% Torulaspora delbrueckii, a wild yeast found naturally in must. However, it must be used in combination with a Saccharomyces yeast to give a completely fermented must.

How do you do it?

How do you add the yeast? It is always dry yeast delivered in a package. It is dissolved in 10 times its weight in 40-degree C water. A regular dose of dry yeast is between 25 and 40 grams per hectolitre of must. Dissolve the yeast in a bowl with the lukewarm water, stir and let stand for 20 minutes. You add as much must to the bowl as needed to bring down the temperature difference between the must in the tank and the bowl with the yeast to below 10 degrees. Then you add this yeasty liquid to the tank, and you do a pumping over so that the yeast is blended properly.

The future of yeast

And the yeast research continues.

Today’s constant search for ways to produce wines with lower alcohol has led researchers to see if they can find yeast that, instead of turning all the sugar into ethanol, turns it into something else. They have already found that specific yeasts can turn a small part of the sugar into either glycerol or lactic acid. However, this brings its own particular problems, so the research continues.

Another branch of research is strains that produces less sulphites (yeast normally do) to reduce the sulphite levels in the final wine.

Read more on: