The wine maker needs a strategy, knowledge and experience, as demonstrated Oenoforo’s experiment

About two years ago I was in Tuscany to harvest grapes. Syrah grapes. There are actually a fair amount of syrah planted in Tuscany. But this was a bit special. We were to harvest seven tons, which is about to one and a half or two hectares. 7000 kilograms, about 7000 bottles of wine to be made.

The grapes were to be loaded in a refrigerated container and then trucked up to Sweden where they were to be vinified. It was an experiment organized by one of the largest Swedish wine importers, Oenoforos.

You can read more about this:

- A Swedish winery? Making Tuscan wine? Yes, indeed! | Per on Forbes: The Crazy Swedish Wine Project, The Greek, The German, And The Italian

- Making wine in Sweden from Italian grapes, another curious project from Oenofors

- A wine importing success story | Per on Forbes: How He Became One Of The Most Successful Wine Entrepreneurs In Scandinavia

The grapes were vinified in Oenoforo’s winery in Simrishamn, the Nordic Sea Winery (that is by the Baltic sea), and the wine has since been aged in a tank and barrel. The idea was that it would be aged for about two years and then sold at auction for a charitable purpose to benefit the Baltic Sea.

In other words, it should now be time to bottle the wine, if it has not already been done.

But the project was also an opportunity to try, on a small scale, different methods and techniques in the wine production.

Does it matter if the wine ferments or is aged in an oak barrel or steel tank? What will the difference be if you use an amphora?

When making red wine, you usually de-stem the grapes before they start to ferment. In recent years, however, it has become popular among winemakers to experiment with keeping all or some of the stalks. It is said that, for example, it may add some extra tannins, and help stabilize the wine, but it is important that the stems – and not just the grapes – are really ripe. But does it really make a difference?

Maybe also the idea of the winemaker, Gerd Stepp, and the founder of Oenoforos, Takis Soldatos, was also to get some new experience on a small scale, which in the future might be useful for improving other wines they make together.

About halfway through ageing time, ie last year, we were given the opportunity to taste a few different variants of this experiment.

We got six different bottles labelled with mysterious codes. All bottles were made from the syrah grapes we picked in Tuscany, but they had been treated differently in the winery.

Was there any difference between the wines?

There certainly was. There were no huge differences, the raw material and the origin were the same, but, of course, the wine had developed differently depending on what the wine maker had done.

Here’s what we found:

#1444

#1444 was the code on the bottle. 60% whole bunch, 40% destemmed. Kept on Chassin barriques, 225 l (Jupille 2014).

Per: Some oak character, but not dominant. Good fresh fruit with strawberry. Supple as soft.

Britt: Soft juicy fruit (berries), with fairly low acidity. I lacked a bit of structure. The oak was balanced.

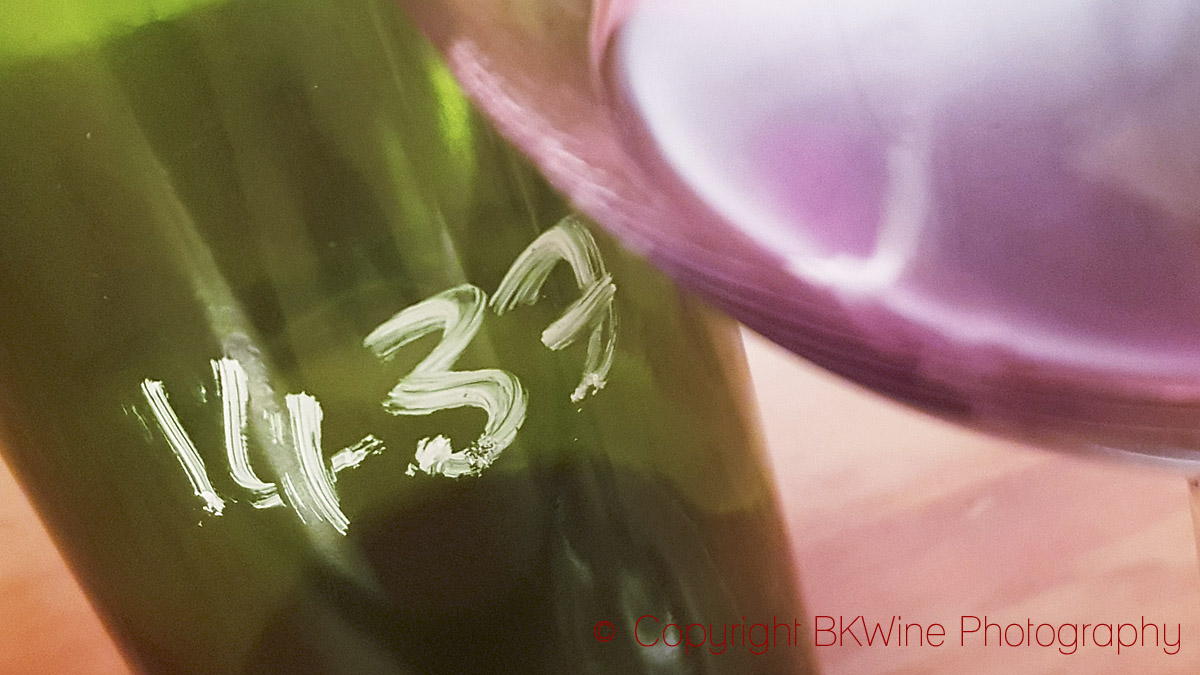

#1437

100% destemmed, Migliara (the name of a particular field where these grapes came from). Kept on Chassin barriques, 225 l (Jupille 2014).

Per: Tighter and drier, spicy, good structure, some toasted notes. Good volume in the mouth with nice fruit. Good tannins and well balanced. The best of the six versions

Britt: More structure and acidity here. Fairly light in style but very nice. Good body and with elegance.

#53

50/50 whole bunch and destemmed. Kept in 500-liter terracotta amphora from Italy.

Per: Spicy, with possibly a slight reduction on the nose. Also on the palate it has a hint of reduction, a bit “hot”, quite short, dry. (Curious this reduction, if it were. One would assume that an amphora added more oxygen and would rather be an oxidative environment.)

Britt: Feels “natural”, a little wild, farmyard, maybe reduced? Dry at the end, otherwise good.

#1600

100% destemmed grapes. Kept in new “Ermitage” oak barrels.

Per: Fruit and in particular berries on the nose with a lot of oak. The oak is dominating. Even the taste is a bit oaky sweetish, but with good tannins with, after all, an OK structure.

Britt: Fine fresh nose and good, classic taste. Quite a lot of oak, fruit and dark berries.

#1438

100% destemmed grapes. Kept on the Chassin barriques, 225 l (Jupille 2014).

Per: Tight and dry, spicy and good fruit. On the palate, very astringent, slightly “hot”, but with good fruit. A slight (not unpleasant) bitterness at the end. The second best wine of the six.

Britt: A very nice wine. A little light, good acidity, the style tends to elegance.

#1443

40% whole bunches, 60% destemmed, Migliara. Kept on the Chassin barriques, 225 l (Jupille 2014).

Per: Good fruit, fairly discreet nose, a little menthol. On the palate, it has an acidity that is a touch sharp and a rather dry rough finish. Could it have been a bit VA? (Volatile acidity.) (VA does not always have to be completely negative. In small amounts it may add some character, but to a greater extent it leads to a defective wine, going towards vinegar. Now if this actually was VA – which I’m not completely sure of – it may also be because it was a tank sample that had been transported to us under far from ideal conditions and had had to wait for a good while before being tasted.)

Britt: Good acidity and fine nose, warm fruit, a little dry on the finish, quite a bit of tannins, hints of farmyard, but quite pleasant.

A very interesting illustration of that small details can make quite big differences. And of that it is important that the winemaker knows what he is doing and has a strategy for where he wants to take the wine.

Now it’s been around two years since harvest so I suppose it’s soon time to bottle and to show the finished product, which will in some way be a blend of all the variants we tried, and some more.