Small Vines Wines is a fairly recent winery in Sonoma, California. A few years back Paul Sloan stood at a cross-roads in his career, should he move to Burgundy to make wine or not? He decided instead to stay in California and make wines inspired by the wines of Burgundy. That was the beginning of Small Vines Wines. With this article we introduce a new guest writer on BKWine Magazine, LM Archer, who met with Paul Sloan at his winery.

“The best fertilizer is the footsteps of the farmer” – Old French proverb

Paul Sloan knew two things growing up on a ranch in Sonoma, California: he wanted to work for himself, and he didn’t want to work in an office. He wanted to work outside.

At age 21, a chance encounter with a glass of 1978 Domaine Romanée Conti La Romanée ignited a passion in Sloan, an all-consuming passion to understand all he could about wine making, and someday create his own grand cru-inspired wines.

It’s safe to say Paul Sloan of Small Vines Wines is well on his way to achieving his goals. Today, Rajat Parr of Domaine de la Côte and Sandhi and co-founder of In Pursuit of Balance, deems Sloan “a pioneer in the vineyard”, while wine writer Michael Cervin includes Paul Sloan on his list of Top 100 Most Influential US Winemakers.

Recently, I met up with Paul and Kathryn Sloan at their estate vineyard in Sebastopol for an informal conversation about building vineyards, growing wine, and the importance of small vines.

What inspired you to get into wine making?

I was in school, working as a wine steward at John Ash & Co. One night, a customer ordered a bottle of 1978 Domaine de la Romanée Conti La Romanée, and asked me if I’d ever tasted a wine like it before. All I could think of was that I had just spent my last $10 on gas to get to work – I doubted I’d ever be buying a $3500 bottle of wine, let alone taste it. When I politely answered ‘No, I haven’t, sir,” he poured me a glass, and told me to savor it – to drink it slowly, and pay attention to how it changed throughout the night. I did. I still had half a glass left at the end of my shift. I couldn’t believe a wine could have such an intellectual impact upon me.

I started reading every book about wine and wine making I could get my hands on, and enrolled in the viticulture program at Santa Rosa Junior College. For the first time in my life, I was earning 4.0 grades in chemistry, botany, etc. Before that, I was always a C student, not because I was stupid, but because I was bored. Eventually, I got my degree in Viticulture and Enology from Cal Poly, and went to work for Warren Dutton before starting Small Vines.

It’s been an amazing journey – eighteen years growing vines, and twenty-three years since leaving John Ash & Co.

Talk about Warren Dutton‘s impact as a mentor in your life.

I met Warren when I was studying Viticulture & Enology at Cal Poly. He hired me to work for him planting vineyards.

I think Warren saw a lot of himself in me. He was already a pioneer in Sonoma wine growing. He and Steve Kistler helped introduced Chardonnay to the region in the late 1970’s. I would tell Warren about my plans to create a vineyard based upon Burgundy’s grands crus standards, but applied to California soils and weather.

One day Warren told me: “Paul, you need to do one of two things: Either move to Burgundy, learn French, and study wine making in Dijon, or stay here, plant vineyards, and bring the Old World to California.”

My wife Katherine and I stayed in California, and Warren guided me in a career planting vineyards for other people, until I could afford to buy my own vineyard.

How do you go about ‘building’ a vineyard?

My uncle was an architect. From him, I learned that architecture is all about looking at your environment. It’s also about understanding ’cause and effect’. Every decision made has an impact on the end result. This applies to vineyards as well. Every vineyard made, you’re making an 80-100 year decision. That’s what they did in Burgundy.

I have planted over 40 sites, and walked away from over 100 more. I’ve walked away because the site did not match the intended use. They should have been growing tomatoes, not vineyards. The soils were too vigorous for vines. Building vineyards is about figuring out each site, then matching the farming or vines to the site.

You made a leap of faith to buy your own vineyard, Small Vines in Sebastopol in 2007. What about the site caught your attention?

Katherine and I looked at 273 properties before purchasing Small Vines. It has everything we’d been looking for: the right climate, a cooling afternoon breeze, and low vigor soils, mostly sandy clay loam and soft sand.

Once we bought the site, we started implementing viticultural standards similar to those of Burgundy’s grand crus, standards put in place to maintain quality. But California isn’t Burgundy, so we have had the freedom to adjust.

We try not to be too dogmatic in our approach, because every harvest is different. We just try to make the best decisions with everything in mind, looking at putting a higher level of thought into what we do.

What adjustments have you made to your own vineyard at Small Vines, and why?

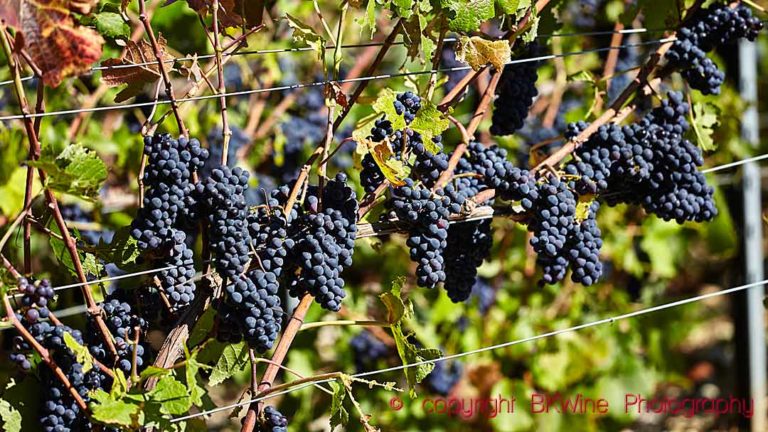

I’m trying to follow Burgundy’s grand cru standards, but adjusting them to accommodate for California’s sun and soils. We use tighter spacing, which results in smaller vines, which produce lower yields with tinier berries and clusters. These smaller berries have thicker skins, resulting in leaner wines with more structured tannins and great aging potential.

Burgundy is built for horses [plows], plus they use 18″ wires [for radiant heat] (footnote 1). Both [Burgundy and California] have the same harvest times around late September, but California’s growing season starts in February or March; Burgundy’s starts in April.

In California, most vineyards use 5’x8′ or 6′x9′ spacing with 36″ VSP (vertical shoot positioning) wire heights (footnote 2) that allows for the tractors to get through, and to produce a good quantity of the vines, which translates into good economics, or ‘production agriculture.’

At Small Vines, the vines run north-south, with 3’x4′ spacing and 24″ vertical-shoot-positioning (VSP) wires. We use irrigation only at the outset. By the time the plants reach age seven, we’ve found that the roots have dug deep enough for dry farming.

Last year I made 32 passes in my vineyard. That means touching every vine, sometimes with tweezers. In contrast, other vineyards in the area may have made only 6-8 passes. My method is 3.5 times more expensive than typical ‘production agriculture’. But it also eliminates the need for fruit drop three weeks before harvest. This is the distinction I’m trying to make between farming vs. ‘growing wine’.

If you do what you need to do in the vineyard, ideally you have little to do in the cellar.

Talk about your approach in the cellar, how does it match your approach in the vineyard?

Every year different, which is what’s exciting – it’s not a cookie cutter craft – we’re creating a piece of art from what Mother Nature provides each vintage.

Terroir is the fingerprint / calling card / identification of a site. Pinot Noir is the most nuanced varietal.

My goal is to preserve that site expression. All my decisions are made to preserve, not manipulate.

For example, using oak as ‘spice’ to enhance a wine, rather than as a flavor ‘change agent’ that smothers it.

In California, a typical mind-set [sometimes] is to ‘erase vineyard flaws’ in the cellar – like letting the fruit hang too long to ripe, then adding back water and acid. This process stomps out the ‘fruit forward’ taste, but only allows for 3-5 years aging. I don’t want to add anything to the wines.

In Burgundy, they want to make wines that draw you in, that can age, that pair with food. They don’t want wines that stand out. They want wines that make you think. It’s more about a cerebral experience, an artful expression of place preserved over a period of years.

Footnote 1: 18” refers to the distance from the ground to the first wire. A low trellising meant to benefit from the reflected heat from the ground.

Footnote 2: 36” VSP refers to the total height of the canopy.

In a few days we will publish a Part 2 with tasting notes on the wines.

LM Archer is a freelance writer based in Seattle and California. She is Francophile who considers wine an art and Burgundy the centre of the universe. She is the founder and editor of binNotes | redThread.