Why do we no longer drink sweet wines? The Swedish monopoly Systembolaget recently presented the market situation for sweet wines and fortified wines in Sweden. It is catastrophic. And perhaps illustrative of what happens in other countries too.

Sweet wines disappearing?

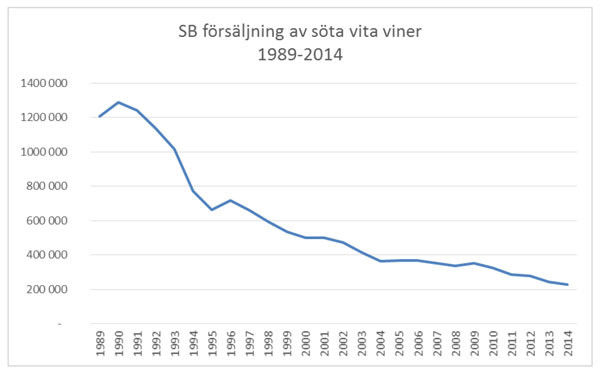

Over 25 years the consumption of sweet wines has fallen by around 85%. In 1989 Systembolaget sold nearly 1.3 billion litres. In 2014 sweet wine consumption is down to around 200 million litres. However, consumption has shifted towards better wines. In 1989 Systembolaget classified 93% of the sweet wines as “simple quality” and only 6% as “higher quality”. In 2014 a full 67% were classified as “higher quality”.

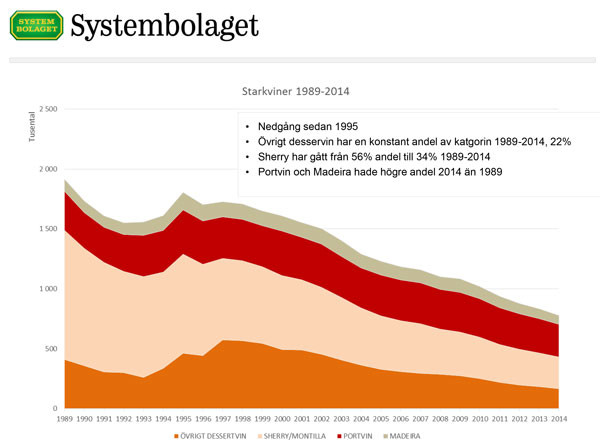

(The following graphs have Swedish captions but I think you will understand what they illustrate anyway.)

Sweet wines are, as a reminder, wines with substantial residual sweetness without being fortified with spirits. It is, for example, Sauternes, sweet German wines, Vin Santo, Recioto and so on.

Fortified wines on a downhill slope

The consumption of fortified wines is also falling dramatically although not quite as much. Fortified wines are wines to which alcohol has been added to stop the fermentation when there is still some sugar left in the wine. They are usually around 18-20% alcohol content. It can be, for example, port, sherry and madeira.

Since 1989, consumption of fortified wines has fallen by two thirds. In 1989 we drank nearly 2 million litres of fortified wine. Today (well, 2014) it is down to around 700 000 litres. The most dramatic fall began in 1999.

But not all fortified wines are equal.

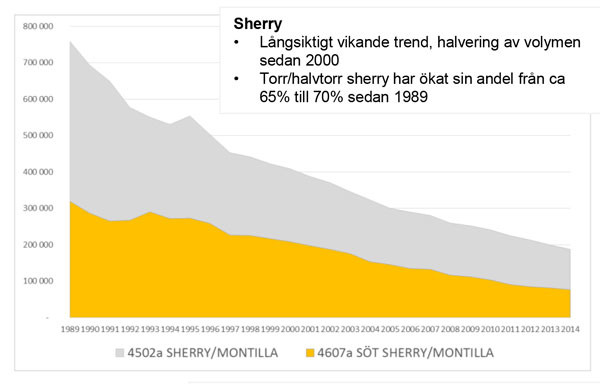

Pure disaster has struck sherry. (Sherry figures also include dry sherry, which of course is the most delicious variant of sherry.) Today, we consume only 25% as much sherry as we did, 1989. Three quarters of the consumption has disappeared.

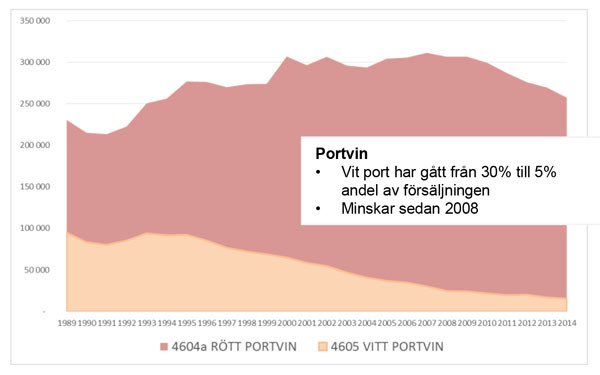

Port wine, however, looks fairly healthy. Since 1989 consumption has risen from around 230,000 litres to more than 250,000 litres, although it has now started to go down from a peak in 2008 of over 300,000 litres.

There has also been a major shift from white to red. At the beginning of the period white port wine had a 30% share of consumption. It has now fallen to be only 5% of all port.

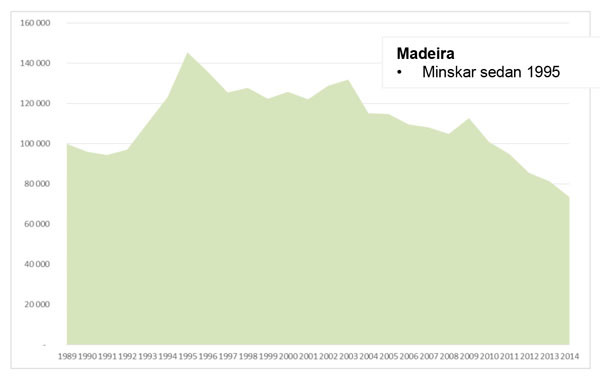

Madeira has in recent years attracted some attention in the press. But this seems not to have had any positive effect on consumption. Madeira had its (most recent and relative) heyday during the second half of the 90s with an increase up to almost 150,000 litres (what really happened in 1995?). But over the full period Madeira has fallen from 100,000 litres to 70,000 litres, I.e. it has lost 30%. In comparison perhaps not that bad.

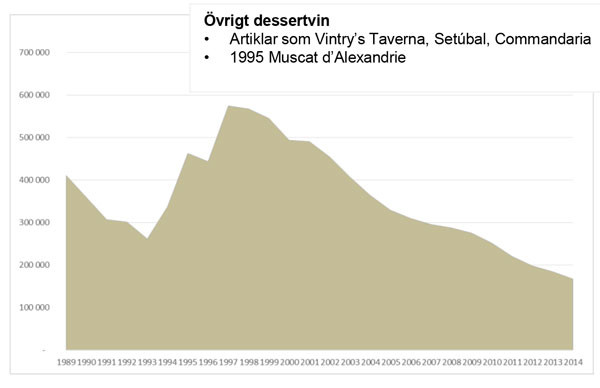

“Other” fortified wines have fallen by more than half, from 400,000 litres to around 170 000 litres. The category includes wines like e.g. Vintry’s Taverna, Setubal (Portugal), Commandaria, Muscat d’Alexandrie etc. But here you also find the exquisite fortified wines from the south of France, the so-called VDN wines (vin doux naturel): Rasteau, Banyuls and others.

Also for these wines there was a remarkable peak in the second half of the 90s, but offset with some three years relative to the peak in port wine. Strange.

Makes you wonder what happened in the mid 90s.

Sherry is the biggest loser, port is a relative winner

At the beginning of the period, in 1989, sherry was the dominant wine with 56% of the entire market for fortified wines. Today sherry has fallen to second place among fortified wines with only 35% market share (less than 200 000 litres).

The winner, both in absolute and relative terms, in the fortified group is instead port which today is the largest category, selling around 250,000 litres annually, 25% more than sherry.

“Other fortified wines” comes third with around 180,000 litres. Madeira is by a wide margin last of the four with about 75,000 litres.

If we go a little bit further back in time the change is even more dramatic. Looking back to 1920 69% of all wine imported to Sweden was fortified wine. At that time, Sweden was probably also the largest export market for Madeira. Almost 40% of all madeira exported went to Sweden.

What will you do about this?

The big question now is: What will you do about this?

Open a bottle of Sauternes with the foie gras?

Take an extra glass of port wine with the Christmas nuts and stilton?

Start dinner with some toasted almonds and olives with a glass of sparkling dry sherry?

Or do yo have any other suggestions?

For we cannot let these fantastic wines disappear!

All data and charts come from a Systembolaget category presentation.

[box type=”info” style=”rounded” border=”full”]Why not dive deep in some of these wines? For example, if you really want to get to know port wine then you should come on a wine tour to the Douro Valley with BKWine.

Travel to the world’s wine regions with the experts on wine and the specialist on wine tours.

Travel to the wine with those who want to share with you some amazing experiences (rather than with those who just want to sell you their wines). Travel with BKWine.[/box]

2 Responses

What about opening the graphs a bit more? Even if they represent only one market region and one retailer, they do reflect the trends of Global consumption habits of these product groups relatively well, and therefore I find useful to analyze the results more thoroughly

I don’t think anyone working on the international alcohol trade really gets surprised about these statistics. This development has been visible for some time. Regardles the change of the total consumption either way, the trend has been towards easier consumption, that is wines with less sugar (offering more varied use with or without food etc.) and less alcohol (less energy, less intoxicating effect so that you can happily drink more). Complex, fullbodied wines need also more time to be apprecieted fully, and as we do not have that much time or effort normally, more linear and accessable alternatives are favoured.

I would like to know more how the category “sweet wines” is defined in the statistics here. My hunch from the Finnish monopoly Alko Inc. and its sales is that, while the consumers have turned towards drier wines, the biggest losers has been inexpensive, mass-produced sweet white wines. If they are all in the same category with Sauternes, Trockenberenauslese and all the other famous names, it’s difficult to draw any definite conclusions. Personally, I think the consumption being moved towards higher quality on the cost of quantity is basically sane.

Some time ago, I read a story about a former Gentlemen’s Club in London which required its members stamina enough to drink three bottles of port in an evening. One of the older members did five, and when he was asked if he really drank them alone, he answered no. “I drank them with a help of a bottle of Madeira.” I would not plan my production based on that kind of consuming habits, though, for that gentleman and his peers are long gone west. There simply is no future for bulk Madeira or Port.

Instead, people are interested in stories of genuineness, and those are what they buy. In the light of these statistics, it seems that the port wine producers has managed to mediate their story to the consumers better than, for example, their colleagues in Jerez. A beautiful landscape does no harm, either.

Yes, I agree, this is probably similar to what happens in most countries.

I don’t know how they define “sweet”. Most likely simply as wines above a certain sugar level in the wine.

A curious “counter trend” is the popularity of sweetish table wines though, primarily red “dry” wines with a substantial amount of RS (8-15 g). There’s been a lot of discussions about that in the press recently. On the other hand, that is perhaps not really anything new.